Years ago, while still living in California, I began my writing career by submitting feature articles to local magazines in the San Francisco Bay Area. For some reason, I always gravitated toward offbeat subject matter, which apparently made my stories interesting – and desirable.

One day, at the request of my editor, I sat down to write a feature story about one of the local towns in our area. But as I started writing, it occurred to me that I really didn’t know what a feature story was, even though I’d been writing them for several years. Wikipedia, by the way, defines a feature story as a “human interest” story that is not typically tied to a recent news event. They usually discuss concepts or ideas that are specific to a particular market, and are often pretty detailed.

Anyway, I grabbed the dictionary off the shelf (this was years before the Web, and digital dictionaries were still a dream), and searched the Fs for ‘feature.’ I read the entry and satisfied my need to know and as I started to close the book, that’s when I saw it. Directly across the gutter (that’s what they call the middle of the open book where two pages come together) was the word ‘feces.’

Now I’m a pretty curious guy, so I wasn’t going to let this go. Needless to say, I know what feces is, but what was really interesting were the words at the bottom of the definition. The first one said, ‘See scat.’ So I turned to the Ss and looked up scat, and it turned out to be the word that wildlife biologists use for animal droppings. But wait, as they say, there’s more. THAT definition told me to see also, Scatologist. (You’ve got to be kidding me). But I did. You guessed it—someone who studies, well, scat.

So I called the biology department at my undergraduate alma mater, the University of California at Berkeley. When somebody answered the phone, I asked, ‘Do you have a … scatologist on staff?’ Of course, she replied, let me connect you to Dan. The next thing I knew I was talking with Dan, a very interesting guy, so interesting, in fact, that the next weekend I was with him in the hills, collecting owl pellets and the droppings of other animals to determine such things as what they eat, what parasites they might have, how predation of certain species affects populations of others, and so on. It was FASCINATING.

Remember that what got me started down this rabbit hole was the search for feature, which led me to feces. Well right underneath the suggestion that I also see scatologist, it said, see also, coprolyte. This was a new word for me, so off to the Cs I went, in search of it.

A coprolite is, and I’m not making this up, a fossilized dinosaur dropping. A paleo-scat, as it were. I have one on my desk. OF COURSE I have one on my desk. Anyway, once again, I got on the phone, and this time I called the paleontology department at Berkeley, and soon found myself talking to a coprologist – yes, there is such a person. How do you explain THAT at a dinner party? Anyway, he agreed to meet with me, and once again I had one of those rare and wonderful days, learning just how fascinating the stuff is that came out of the north end of a south-bound dinosaur. He showed me how they slice the things on a very fine diamond saw and then examine them under a high-power microscope to identify the contents, just as the scatologist did with owl pellets and coyote scat.

Think about this for a moment. If I hadn’t allowed myself to fall prey to serendipity (Wikipedia defines it as “A “happy accident” or “a pleasant surprise”), I never would have met those remarkable people, and never would have written what turned out to be one of most popular articles I’ve ever written.

Another time, my wife and I were out walking the dogs in a field near our house. At one point, I turned around to check on the dogs and saw one of them rolling around on his back the way all dogs do when they find something disgustingly smelly. Sure enough, he had found the carcass of some recently dead animal, too far gone to identify but not so far gone that it didn’t smell disgusting. I dragged him home with my wife following about 30 feet behind and gave him the bath of baths to eliminate the smell. Anyway, once he smelled more or less like a dog again I felt that old curiosity coming on, so I went downstairs to my office and began to search Google for the source of that horrible smell that’s always present in dead things. And I found it.

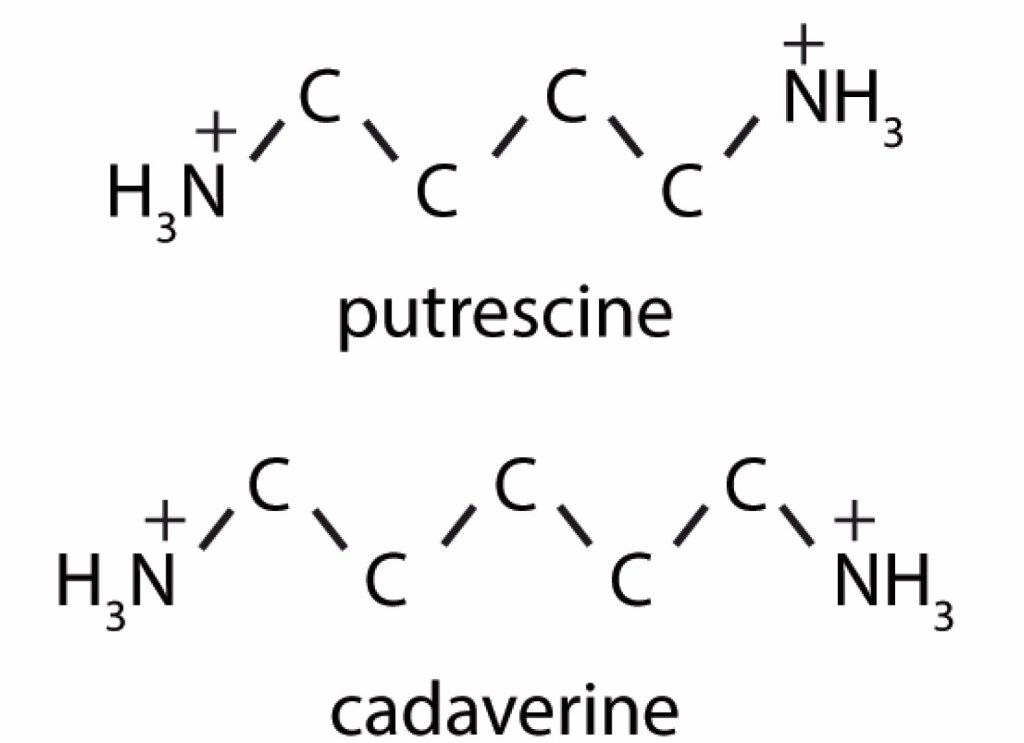

The smell actually comes from two chemicals, both of which are so perfectly named that whoever named them clearly had a good time doing so. The first of them is called cadaverine; the second, putrescine. Can you think of better names for this stuff? Interestingly, putrescine is used industrially to make a form of nylon.

So what’s the point of this wandering tale? Storytellers are always looking for sources, and the question I get more often than any other is about the source of my stories. The answer, of course, has lots of answers, but in many cases I find stories because I go looking for them but leave my mind open to the power of serendipity. For this reason, I personally believe that the best thing about Wikipedia is the button on the left side of the home page that says, “Random Article.” I use it all the time, just to see where it takes me.

Curiosity is everything. I just wish there was more of it in the world.