I make occasional trips to a small pond near my home, a place called Mud Pond, which is really a flooded peat bog. I love it, because it’s close—it takes me five minutes to get there—and because it’s a diverse mix of ecological zones. During a 15-minute walk I can wander through deep conifer and deciduous forests, a delicate riparian zone, and I can walk along a chattering, rocky brook as it makes its way to the pond.

The forest there is a gentle, quiet place during the day, and in the summer, it’s a green cathedral—my idea of church. Birds sing; the wind sighs and mumbles through the branches; the stream giggles over the rocks with a voice like a crystalline wind chime. Otherwise, it’s pretty quiet.

Night, on the other hand, is a different story. That’s where I am right now. I’m sitting here, in the dark, deep in the forest. It might be because there’s no moon, and the darkness has wrapped around me like black velvet, but there are sounds, all around me, none of which I hear during the day. Branches crack and fall with a sound like collapsing Tinker-toys, a sound that’s amplified by the darkness. Small things scurry and forage in the leaf litter, and they sound a lot bigger than they are. Somewhere overhead, a screech owl lets loose, and my heart skips beats. Mountain lions come to mind.

I’m wearing a headlamp, and when it’s turned on, it projects a cone of light ahead of me in the darkness. Flying things, insects and bats, flit through the beam, instantaneous and momentary shadow shapes that are unnerving. They remind me of my days as a professional SCUBA diving instructor, when we did night dives in the Pacific Ocean. Until we extinguished our lights—an act of faith of the highest order— and allowed our eyes to grow accustomed to the darkness, we were blind. And even when the lights were on, the only piece of the ocean that we could see was whatever found its way into the cone of light created by our dive lights. All too often, we’d find ourselves in a game of chicken with a harbor seal or a California sea lion. Attracted to our lights and naturally curious, they’d swim down the light beam like a runaway locomotive, veering away at the last possible moment, disappearing into the sea. You never—EVER—forget the first time that happens.

The forest at night is calm, sometimes loud, gentle, often violent, friendly, mysterious, and more than a little terrifying. I’ve stopped to sit on an old fallen tree that’s slowly disappearing into the ground as it returns to the soil. I’ve turned off the light and closed my eyes to take it all in. Eyes open; eyes closed. Nothing changes. The darkness is absolute, but the sounds are all around me. My eyelids make no difference whatsoever, and I have no earlids, so the sounds of the forest are ever-present. A bat whooshes so close to my ear that I feel the wind as it passes. It sounds like a falling envelope.

I slowly grow accustomed to the fact that I’m alone in a dark forest, where my only company is the trees, the mosses, the ferns, the rotting biomass, and whatever unnerving thing is rustling around in the leaves behind me. The smell is deep and rich, slightly foreign, the incense of the forest cathedral. Looking around, I see nothing; I look to the sky, to the treetops, and see the same, although I can just make out the silhouettes of branches against the dark sky.

But when I look down, I see—something. There’s light down there. I can barely see it, but it’s definitely there. Squatting down, then on hands and knees, I move in for a closer look. Clinging to the bottom of the rotting log, in a clump about the size of my fist, is a cluster of small, pixie-capped mushrooms. And they’re glowing in the dark. They aren’t bright; it’s nothing I could read a book by, but they glow.

There’s something intellectually wrong about this glowing mass at my feet. This should not be happening. These are mushrooms, and they’re glowing in the dark. In spite of the fact that I’m struggling to wrap my head around a glowing fungus, I’m no neophyte; this isn’t the first time I’ve experienced bioluminescence. As I said, I used to be a SCUBA instructor. I often taught advanced classes, during which I put the students through their paces to earn a higher-level certification. Over the course of a grueling long weekend, they had to perform a deep dive, a rough water dive, and a salvage dive, during which, if they completed the exercise, they’d successfully bring a large sunken case to the surface, where they would find it to be filled with iced beer, champagne, soft drinks, and snacks. They also had to demonstrate proper underwater navigation skills by swimming a complex compass course, the proper execution of which would take them to a very non-natural formation on the bottom of Monterey Bay called The Bathroom. Years ago, someone dumped a claw foot bathtub, a pedestal sink, and a toilet overboard. Divers gathered the pieces, set them up on the bottom, and, of course, took all of the appropriate photographs of themselves bathing in the tub, brushing their teeth at the sink, and sitting on the toilet. There was no ambiguity about whether a diver succeeded at the navigation dive—they either arrived at the Bathroom, or they didn’t.

The final activity in the program was a night dive. The group would gather in a sloppy, floating circle on the surface, and vainly try to create a sense of collective courage before releasing the air from their vests and descending into the unknown blackness of the dark ocean. Once they arrived at the bottom, they were instructed to turn off their lights, which they reluctantly did. The ocean swallowed them; the darkness was utterly complete.

Initially, they’d see nothing, because their eyes had not yet acclimated to the darkness. After a minute or so, though, as pupils expanded and retinas began to fire in overtime, they’d begin to make out the ghostly, shadowy shapes of rocks and kelp forest and the decaying pipes from the old canneries on shore. And then, in a moment never to be forgotten, magic would strike. One of the divers would collect her courage and push off the bottom, like a fledging bird. The instant she moved, the ocean would catch fire with the sparks of bioluminescent plankton annoyed by the moving water column, a sparkling constellation of biological stars. It was beyond breathtaking. A sweep of a hand through the water left a wash of light like an underwater sparkler; kicking fins left a glowing contrail. It was the most fitting graduation ceremony I could imagine, the earth’s original light show, a microscopic celebration of life.

How appropriate it is that the compounds responsible for this cold light are named for Lucifer, the dark lord, the fallen angel. His name means ‘bringer of light,’ and, just like its namesake, biological light is appropriately otherworldly. And it is indeed cold; 80% of the energy consumed in the generation of bioluminescence creates light; only 20% becomes heat, which is far more efficient than today’s best LED lights, which create 85% heat and 15% light from the energy they consume. Even Shakespeare, in Macbeth, jumped on the Lucifer bandwagon: ‘Angels are bright still, though the brightest fell.’ Into the ocean, apparently.

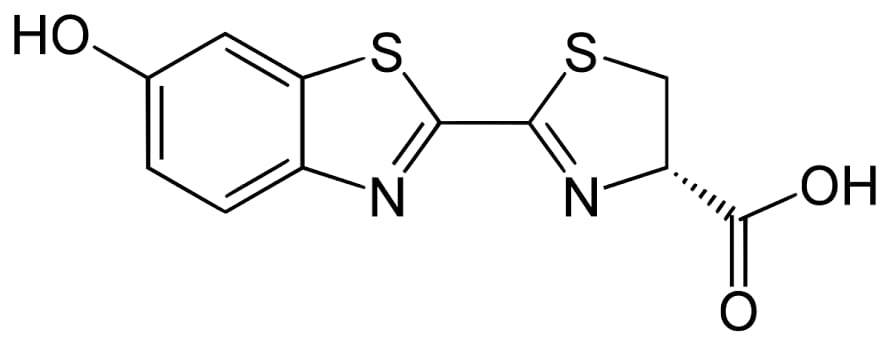

This luminance occurs when two compounds are combined: Luciferin, the substrate that forms the foundation for the reaction; and Luciferase, an enzyme that accelerates the oxidation of Luciferin, a byproduct of which is the light from the mushrooms at my feet—and from the plankton that my divers disturbed during their night dive. It occurs naturally, and all over the world. In New Zealand, bioluminescent glowworms dangle by the tens of thousands from the ceiling of the Waitomo Cave system, like glowing blue spaghetti.

Strangely, the phenomenon results in a host of emotions. I met a man at Mud Pond the other day who will not venture into the woods after dark. He isn’t afraid of animals, which is the fear that most people have; I won’t go there because things glow there, he told me.

I myself am fascinated, and enchanted, and unnerved by the faerie-fire at my feet. I covet this strange light—I want it. A part of me wants to gather the mushrooms and clutch them to my chest like Gollum and his ring, my precious, and run shrieking through the woods. Another part of me wants to put distance between us.

As a biochemistry student at Berkeley years ago, we filled test tubes with light by mixing hydrogen peroxide with dye and a phenyl oxalate ester. Chemically different from Lucifer’s light, it’s equally enchanting (this is the stuff that makes the chemlight sticks that people wave at rock concerts work). Chemical light can be manufactured, but it is a far more elegant undertaking to bioengineer living creatures to glow in the dark. By splicing a specific jellyfish gene into the genetic matrix of the mouse, scientists have created glowing green rodents. And while bioluminescent mice aren’t everyone’s cup of tea, imagine walking through a bioluminescent forest at night, a place out of Avatar’s Pandora. Imagine a city where bioluminescent trees and bushes replace electric streetlights, where glowing, multicolored lichens and mosses and flowers encrust the walls of buildings, and where shimmering grasses carpet everyone’s lawn with flowing waves of light. Imagine if plants could signal their need for water or nutrients by glowing in a particular way, or signal distress by flashing on and off in a specific pattern, a visual, biological SOS, an early warning system against infestation.

So I’m still lying flat on the ground, and I tentatively reach out and touch the glowing fungus at the base of the log. I don’t know what I expect; maybe some kind of a reaction, a subtle shift in colors in response to my approach. Or perhaps I expect warmth; but no, it’s just as cold as any other fungus. This incongruity of cold light is beyond understanding; it defies logic. I can look at the complex diagram of Luciferin’s structure on my phone, its string of intricately interconnected carbon rings, strung with molecular bangles of sulfur and nitrogen and hydroxyls; I can even follow the oxidation process that takes place during its dance with Luciferase that yields light. That doesn’t mean I have to believe it, though. This is faerie fire, plain and simple. There are faeries about in these woods, or perhaps Pandorans; I just haven’t found them yet.