How many times during your career has someone said to you, ‘Do what you love. The money will follow.’ I know I’ve heard it, many times. And while it’s a wonderful sentiment, it isn’t entirely true. Not entirely. I’ll come back to that in a minute. But throughout our lives and careers, well-meaning people share advice with us—aphorisms, for lack of a better word—intended to keep us on the straight and narrow path to success. Some of them are true; some of them are partially true; and some of them are decidedly wrong.

I find myself in an interesting place: I’m retiring. There—I said it. I’m leaving behind the carefully planned, strategically executed career I’ve had in telecommunications that began in 1981. And if you believe that part about ‘carefully planned and strategically executed,’ then I suggest you ask your physician about an update on your meds.

I’ve been lucky throughout my career to have had friends and mentors, villains and heroes, and inspirational, quirky characters along the journey who showed me the way forward—or perhaps better said, different ways forward. I took something away from all of them, something valuable, even when the recommendation or suggestion or advice was ill-advised. I know people are supposed to say those kinds of things at their retirement party, the one where the company used to give you the gold watch. But I’m not going to have one of those. For me, retirement happens to coincide with my birthday later this year, so instead of a gold watch, I’m giving myself the gift of time. And as for all those characters I’m supposed to mention? They were real for me, and I’m grateful to all of them for the many things they taught me along the way. So: As a gift to all my friends and colleagues, as a form of paying it gratefully forward, I want to share some of those things I learned with you. I hope you find them helpful.

By the way, retirement, for me anyway, doesn’t mean sitting in a rocking chair on the front porch waiting to keel over. It means doing more of the things I want to do—spending more time with family and friends, and devoting more time to writing, a bit of speaking, and recording audio.

My career and the way it coincided—collided? —with my passions was an exercise in the purest form of serendipity. Serendipity: ‘a happy accident,’ according to various dictionaries. Like many kids during the Shiftless Seventies, I had no idea what I wanted to do with the rest of my life once I graduated from high school. Granted, I was a special kind of screwed up, because I went to high school overseas as a result of my dad’s work—an incredible, priceless experience—but when I came back to the States for university, I went through what at the time were the poorly understood reentry challenges that people have when they return to their home country after an extended period abroad. I couldn’t fit in, and I had a very hard time making friends because I had so little in common with my peers. I listened to different music, spoke multiple languages, watched different sports, dressed differently, and was acculturated to living under the dictatorship of Generalísimo Franco. What could I possibly have to talk with them about? It wasn’t until much later that I began to understand what I was dealing with and how to handle it; I even wrote a book about it to help others who were facing the same challenge. A big part of my initial independent consulting work was with companies that needed to build reentry strategies for their returning expat employees.

All that to say that I was personally and culturally discombobulated. I went to Cal Berkeley and got a degree in Spanish because it kept me emotionally connected to Spain, the place that was now the home that I identified with more than any other. I also earned a minor in marine biology because I’ve been a biology geek since I was nine years old, and I love the water and everything in it.

So, upon graduation, armed with a degree that qualified me to teach sea otters how to speak Spanish, I became a SCUBA diving instructor, then became a part-owner of a diving business in the San Francisco Bay Area that did underwater photography, commercial diving, sold dive gear, and certified new divers by offering eight-week classes that took place in the classroom, the pool, and the ocean.

Of all the things I did as part of that job, teaching was what I loved the most. In fact, I got a commendation from the certification agency for certifying more new divers in a single year than any instructor ever had before. I loved it—I loved seeing the wonder bloom on the face of a new diver as they took their first apprehensive breath from the regulator with their face in the water, and saw the wonder that lay below the surface. I also loved the moment when they came close to drowning, as they attempted to inhale from the regulator while smiling broadly. Bad combination.

One of the aphorisms or lessons that was pounded into me early on by quite a few people was this: ‘Do everything you can to get into management. That’s where the money is. And once you get there, be tough. Soft managers are bad managers.’ Okay. Let’s talk about that, because it’s patently false and has misled a lot of people—me included.

In 1981 I left the diving business behind, and with quite a bit of trepidation, joined the high-falutin’ corporate ranks of the telephone company in California. In 1981, AT&T was still three years away from being broken up by the divestiture mandate, which meant that (1) they were a monopoly, and (2) they had a license to print money. They were rolling in it. And I was one of the beneficiaries, because upon joining Pacific Telephone, fully qualified to do so with a degree in Spanish and a single resume entry that said something like ‘jumped in the ocean every day for five years wearing a rubber suit and carrying a tank full of high-pressure air on his back,’ the company deemed me telco-worthy and put me into the first ever Computer Communications Systems Management Training course, or CCSMT to those of us who had the privilege of being selected to participate.

It was a seven-and-a-half month, full-time intensive training program, during which we learned to troubleshoot every analog and digital circuit out there; learned how to operate the mainframes and minicomputers in the data center and how to deal with the dreaded outages that cost the company hundreds of thousands of dollars a minute while the machine was down; learned sophisticated protocol analysis tools and techniques; learned how the telephone network worked (43 years later, it’s still magic to me); and a thousand other technical things that I can’t remember now. They sent us to Bell Labs and Bell Communications Research and the Bell System Center for Technical Education. We went to countless vendor schools. And, we learned about unions, and labor relations, and human resources, and time management, and how to calculate overtime for a union-represented employee who has already worked 48 hours on day shift for the current week of this pay period but has now been called in on night shift to work an additional eight hours on a Saturday because someone is sick, but Saturday is Christmas Eve, so which part of all that is paid at triple time-and-a-half? The landing of the Eagle on the Moon in 1969 was less complicated.

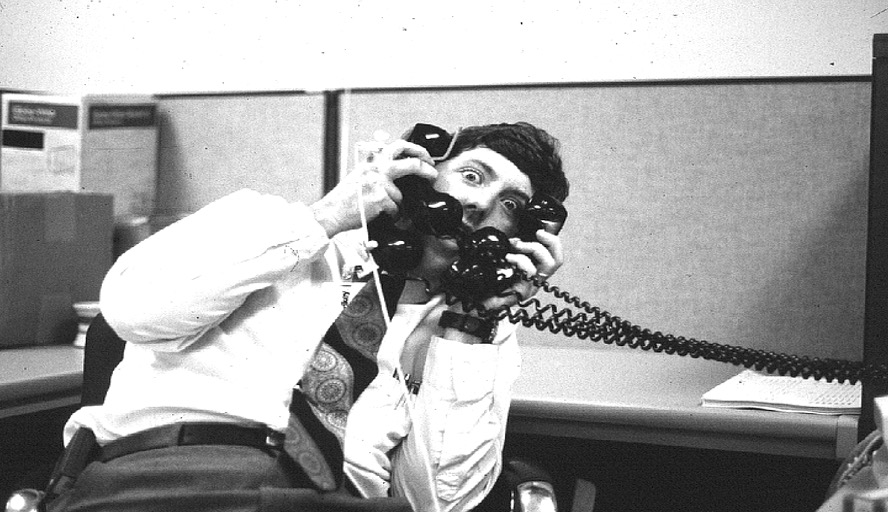

I hated that part. Give me a bad repeater under the raised floor, or a failed hard drive on the mainframe, or a 2,500-pair cable in the field that’s failing because earth movement from a recent earthquake caused the hard plastic sheath to crack and water’s leaking into it, any time. Timecards? Employee rating and ranking? Just shoot me now. That was work for managers.

I’ll admit it now; I didn’t want to go into management, because I liked the hands-on stuff. Manage the diving business? Okay, but I’d much rather be in the ocean certifying divers. Run a computer room? If I have to, but I’d rather be on my hands and knees under the raised floor, looking for the bad cable or determining which component is creating that nasty smell of burning electronics. So, when they finally dragged me into management, I wasn’t good at it. I tried, but my heart wasn’t in it—it wasn’t the least bit inspiring to me. It left me cold. I did it because I had to, as part of the advancement track that everybody talks about. And don’t get me wrong: I learned a great deal being a manager, and I definitely appreciated the pay bump, given that Sabine and I had two little kids, but I know beyond doubt I wasn’t one of those managers who inspire people. I simply wasn’t good at it. And you know what? That’s okay.

Here’s the lesson to walk away with. I learned pretty quickly that success, especially in a corporate setting, is about knowing your own limitations and accepting them with grace, and being good at delegating things to people who are better at them than you are. That means you get to focus on the things you’re good at, and they get rewarded by being recognized for what they’re good at. Oh—and a nice by-product? The job gets done well. It’s called division of labor, and it has worked since the first time two people decided to plant a field together in the Fertile Crescent, 5,000 or more years ago.

Some of you have heard me mention, in previous episodes, my friend and mentor Tom Vairetta. Tom was one of the best managers I ever met—ever. I used to say that the best boss I ever had was a man who worked for me at the phone company. That was Tom. To this day, if I’m facing a difficult challenge, I always ask myself, ‘What would Tom do here?’

One thing Tom taught me was to pretend that every single person I encounter throughout the day, whether they were my own employees or people from other work groups, is wearing a sign around their neck that says, “Make Me Feel Important.” That’s all people want. Everybody matters. Make them feel as if they do and you will have fulfilled 90 percent of the mandate of a good manager. The other part is that timecard thing from hell. That’s NASA stuff.

Here’s another lesson I learned along the way that had significant personal impact that will become obvious to you through the telling. I was often advised by hardcore, career corporate types that ‘Whatever you do, don’t allow the company to EVER move you into training. That’s the dead end of death. Trainers are the walking dead.’

Wrong thing to say to someone whose favorite job so far was being a diving instructor. But it occurred to me at some point that if you put the walking dead in charge of engendering in your employees the skills and capabilities that are required to move the company forward, then how can trainers and educators be the walking dead? Seems to me that that’s a pretty important role. And given that I spent the majority of my career in various forms of education, and I’m still standing, it’s pretty clear that the advice was ill-placed.

Here’s a corollary to that last one. ‘If you love what you do, you’ll never work another day as long as you live.’

Actually, that’s backwards. If you love what you do, you’ll work every single day of the year, and you’ll put in long hours, but you’ll have a smile on your face all day long and at the end of the day you’ll feel energized, not exhausted. I know this to be true from personal experience. In 1991, I left Pacific Bell and went to work for a small but highly respected consulting company based in upstate Vermont. I was recruited to the company by its founder, and man, I was walking on air. Talk about an ego boost! This was a company where we’d walk down the hall of a customer location and after passing a group of employees, they would whisper, ‘Those are Hill Associates people!’ What a buzz.

Working for that company was one of the greatest opportunities of my life, and I’ll be grateful to the founder, Dave Hill, for the rest of my life for taking the chance he did on me. I often described the place as a repository of the smartest people on Earth. Most of them had forgotten more about technology than I would ever know. In fact, I was one of the only people in the company who didn’t have a degree in electrical engineering, computer science, or robotics. I would work so hard to learn a new technology—new to me, anyway—and when I had, when I felt like there was nothing else to learn from reading the standards, when I knew that I was the universe’s expert on that topic, I would make the mistake of having a conversation with someone in the company who actually hadlearned everything there was to know about that particular technology.

Here’s an example. One of my colleagues, who is still a close friend, was once teaching packet switching at Bell Labs. If you don’t know what packet switching is, it’s the basis for how data moves around the Internet—and for that matter, most other modern networks, as well. Anyway, one of the most important algorithms to know about in terms of how data is uniformly and fairly distributed across a network where multiple paths exist between a piece of data’s source and its destination is called Chu’s Algorithm. It’s complicated stuff. My friend was teaching Chu’s Algorithm to a group of propellerheads at the Labs as part of the packet class. During the class, a guy kept sticking his head in the door, listening for a bit, taking a few notes, nodding, and then abruptly leaving. This happened quite a few times. Finally, my friend asked the class why the guy who kept interrupting didn’t just come in and sit down. The class told him that he’s too busy—that’s Dr. Chu. You know, the guy who wrote the algorithm.

That’s what I was up against. But I was a good writer and teacher, and they needed those skills as much as they needed people like my friend who could explain the market implications of Chu’s Algorithm to Dr. Chu.

Anyway, after ten years, I left the consulting firm to start my own business. I had written a book called Telecommunications Convergence, which had become a bestseller, followed up quickly by another book, the Telecom Crash Course, which ALSO became a bestseller. I wanted to write more books and pursue more international work, especially in Latin America. So, in 2000, I left and started the Shepard Communication Group, where I’ve been ever since.

All that to say, here’s another aphorism for you: ‘Find a career and stick with it. If you change careers, or companies, hiring managers will think you’re a dilettante and they won’t hire you.’ Well, that’s outdated advice today. Sure, there’s much to be said for staying with a company, year after year, but only if it gives you as much as you give it. And demographic behaviors are changing.

Interesting word, career: it comes from the Medieval Latin word carraria, which means a road. Isn’t that what a career is? A road? A path to some destination? That’s something to think about.

Here’s a final quote for you that I took under advisement, early on: ‘Anyone can get a job, but your goal should be to find a career.’ Okay—or, you can find a job you love and turn it into a career. What’s wrong with that?

I’ve had the most non-linear career anyone could possibly imagine: dive shop operator, dive instructor, commercial diver, telecom analyst, IT data center manager, telecom educator and advisor, consulting analyst, writer, public speaker, and audio and video producer. Was that a career, or a string of unrelated jobs? I’d love to say that I planned this career, but I’m not that smart, and no one would believe me, anyway. When I think back on the last (wow) 48 years, and reflect on what I’ve already written here, I’d like to share a few things with you, especially if you’re reading or listening to this and you’re in the early stages of your career. Consider this a summary.

I started this essay with the aphorism, ‘Do what you love. The money will follow.’ That’s partially true. There are plenty of things that we all love to do that don’t pay the mortgage, but that doesn’t mean we should walk away from them, because in this life, we get paid in two ways. The salary we earn for doing the job we’re paid to do feeds the bank account; the passion projects we take on, what people used to call hobbies, feed our soul and our sense of personal well-being. Both are valuable, necessary currencies, and a focus on one at the expense of the other does us considerable harm. For example, I produce the Natural Curiosity Project Podcast because I love to do it and because people enjoy the topics I talk about and the interviews I do with interesting people. It doesn’t pay the bills; it feeds my soul, and makes me smile. But the paid audio work I do for clients, often because they’ve heard the Podcast and want something similar for their own purposes, that work contributes to paying the bills in a very nice way. And one more thing: I’m as busy now as I ever was when I was flying and working all the time, because I have lot of things to do that make me happy. But I know many, many people for whom their life is their job. What will they do when they retire? Please don’t fall into that trap. Keep both currencies flowing—you’ll thank yourself later.

‘Whatever you do, get into management’ was the next lesson that older, more experienced corporate types told me. And yes, there’s something to be said for that, if it calls to you—and for many, it does. It just didn’t call to me. I didn’t like it, I wasn’t good at it, and I went in another direction. The message here is this: listen to what others have to say but follow your heart. Is it important for everyone to have management skills? Absolutely! Is it important for everyone to be a manager? Definitely not.

‘Avoid training like the plague.’ Training and education aren’t a job; they’re a calling. If they call, answer. Agreeing to join the Advanced Technologies Training division at Pacific Bell was the decision that put me on the path to what became my amazing, wonderful career. That was how I met Dave Hill, who hired me away from the phone company and moved my family to Vermont; Hill Associates was where I became proficient and comfortable with technology; and Hill Associates was where I wrote my first two technology books, both of which became bestsellers and gave me the confidence to set out on my own in 2000.

And I don’t mean to imply that this advice only applies to training and education. There’s an old and worn-out aphorism that says, ‘Those that can, do; those that can’t, teach.’ Well, somebody had to teach those who do, HOW to do! So, listen to your own advice, and with both eyes open, make your own decision. Your heart and your mind will talk to you; listen to both, but really listen. The heart knows what it wants.

‘If you love what you do, you’ll never work another day as long as you live.’ I’ve lost track of the number of people who have said to me, “You’re so lucky to be independent and work for yourself. You can work whenever you want to.” True: and it’s a good thing I want to work every freaking day of the year, because that’s what happens. Independence does not translate to work-free, or less work. It means that everything is on your shoulders, and while the model worked for me very well, that’s not true for everyone. Be honest with yourself if you should ever entertain the idea of going independent. If you’re okay working long hours alone in your office, traveling alone, staying alone in a hotel, eating alone, and in general just spending a lot of time with yourself, go for it! But if you’re the kind of person who needs to have lots of people around all the time, think twice. I’m not saying don’t do it—I’m simply saying, think about it, and discuss it with those around you who will be affected by the decision.

‘Find a career and stick with it. If you change careers, or companies, hiring managers will think you’re a dilettante and they won’t hire you.’ There was a time when this was good advice, but today, not so much. Between the culture of the gig economy, elements of which have crept into the traditional workplace, the lingering work-at-home effects of the COVID lockdown, and shifts in workplace priority and balance caused by generational change, the practice of routinely changing jobs and companies has become common. But let me make a point here. Companies hire employees because they bring value to the workplace, and that value, more often than not, comes in the form of a well-developed, monetizable skill. Whether you call it a career, a job, or a calling, what matters is that you bring a well-developed differentiable capability that creates value for the company looking to hire you.

And that brings me back to my first point, which is also my last point. ‘Do what you love. The money will follow.’ It has taken me more than fifty years to realize that above all else, I’m a storyteller. Whether I’m standing in front of a classroom, or writing a book, or crafting an article, or assembling a video script, or creating a white paper, or shooting photographs, or producing a Podcast, or directing a video, ultimately, I’m telling a story. I’m creating context for an intended audience. That’s my gift, and I use it to earn a paycheck. Writing, recording, photographing—all of those are paving stones in the road of my career. But let me remind you: I also have many years of expertise in the arcane field of telecommunications, which means that I use my varied storytelling skills to create value for my telecommunications clients. I don’t love telecom; I love telling stories about telecom as a way to convey content and context in the form of communications. That’s the essence of good storytelling.

In my case, the money follows because I have expertise in my chosen field. My passion, the craft of the well-told story, is my differentiator. So, I have the ability to engage in my passions, to do the things I love—writing, speaking, recording, photographing—because I’ve figured out how to use them as delivery vehicles for the things I do that earn me a living. That’s the magic formula.

Do you know the word amateur? In French, it means, ‘a lover of.’ I am a lover of writing, speaking, recording, and photographing, which means that I am an amateur at all of them. And those are the things that make me good at what I do, professionally.

So that phrase should be re-written as follows: ‘Do what you love. It will make you better at doing the things that make the money follow.’ And, it will prevent you from resenting the work you HAVE to do because you’re also doing the work you WANT to do.

So, take the advice of Mark Twain, who is my answer to the question, ‘What famous person would you most like to have dinner with’:

“Twenty years from now you will be more disappointed by the things that you didn’t do than by the ones you did do. So, throw off the bowlines. Sail away from the safe harbor. Catch the trade winds in your sails. Explore. Dream. Discover.”

A few thoughts that I hope you find useful. Stay in touch!