When in the Course of human events it becomes necessary for one people to dissolve the political bands which have connected them with another and to assume among the powers of the earth, the separate and equal station to which the Laws of Nature and of Nature’s God entitle them, a decent respect to the opinions of mankind requires that they should declare the causes which impel them to the separation.

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness. — That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed, — That whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government, laying its foundation on such principles and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their Safety and Happiness. Prudence, indeed, will dictate that Governments long established should not be changed for light and transient causes; and accordingly all experience hath shewn that mankind are more disposed to suffer, while evils are sufferable than to right themselves by abolishing the forms to which they are accustomed. But when a long train of abuses and usurpations, pursuing invariably the same Object evinces a design to reduce them under absolute Despotism, it is their right, it is their duty, to throw off such Government, and to provide new Guards for their future security.

Those, of course, are Thomas Jefferson’s opening lines of the U.S. Declaration of Independence. I’ll be referring back to them throughout this essay, so keep them close at hand.

I am not a political scientist, nor am I a historian or sociologist. Here’s what I am: well-educated, with an undergrad degree from UC Berkeley in Spanish, and a minor in Biology; a Masters from St. Mary’s in International Business; and a Doctorate from the Da Vinci Institute in South Africa, where I studied technology and its sociological impacts across the world. I am well read, averaging 140 books per year, including everything from fiction of all kinds, to poetry, history, geography, travel, narrative essay, biography, technology, children’s books, and biology. I’m well-traveled: I spent my teen years in Francisco Franco’s Spain, I’ve lived and worked in more than 100 countries, and one of my favorite genres to read is the travel essay, which gives me insights into places I haven’t had the opportunity to visit. Finally, I’m a professional writer, speaker, and educator, with more than 100 books and hundreds of articles and white papers on the market.

Here’s how this all sugars off (that’s a Vermont term, by the way, that refers to how we boil maple sap to create syrup). First, I’m ferociously curious. I live to ask the question, ‘Why?’ I’m not satisfied simply knowing what something does, or even how. That quality served me well throughout my career as a consulting analyst to corporate executives, who wanted help with their strategic decision-making processes. I’m not satisfied with something because somebody said it—I want to know why, and I want to know that it’s true. That takes work; it means I have to check my sources and dig into the facts before I accept a conclusion. If more people were willing to do that simple thing, to exercise their right, obligation, and responsibility to be healthily skeptical, to respond to a ‘stated fact’ with, “Are you sure about that? I’m just gonna check one more source to verify,” the fake news issue wouldn’t be an issue. Like it or not, believe it or not, the Earth is not flat, vaccines work and do not cause autism, we really have been to the moon, the universe is expanding, and evolution is a fact, not a theory. Science is science for a reason: because by its very definition, the things it proposes have been exhaustively verified through a rigorous, competitive process of validation. It’s not opinion: it’s fact. Period. Furthermore, news is precisely that—news. It isn’t opinion. Yet in the minds of many, the two are seen as one and the same, and far too many people are willing to just accept what they hear or read without question as an undeniable truth. THAT is an abdication of responsibility as a citizen in a free country. It’s an extreme form of laziness, laziness of the worst possible kind.

When we moved to Spain in 1968, we were indoctrinated in the rules of the expatriate road. Do NOT make public comments about the government. Do NOT criticize any public figure. Remember, you’re living under a dictatorship. Be wary of the police; they are not your friends. There were two television channels, one sporadically broadcasting soap operas and cartoons for the kids for about three hours a day, the other what we called the “All Franco, All the Time” channel—hours and hours of the Generalísimo standing on a stage, waving his arms.

Let me be clear: I loved growing up in Europe; Spain will forever be in my blood. The experience played a large part in making me who I am today, a person entranced by languages, diverse cultures, strange foods, and the allure of travel. But it also put me in a place where I developed the intellectual wherewithal to critically compare the USA to other countries, especially when I started traveling extensively for a living.

America’s involvement in Vietnam was just starting to wind down when I started college. Like so many young people, I was critical of our involvement, because there was no logical reason whatsoever that I could discern for our presence there, certainly no tangible return that was worth the loss of life that that ugly war created. But I remained an ardent supporter of the United States, the Shining City on a Hill, in spite of my disagreement about Southeast Asia.

Years later, I became what I am today—writer, teacher, audio producer, photographer, speaker, observer of the world. I’ve worked all over the planet and have had the pleasure and honor to experience more countries, cultures, linguistic rabbit holes, ways of life, and food than most people will ever see. For that I am truly, deeply grateful.

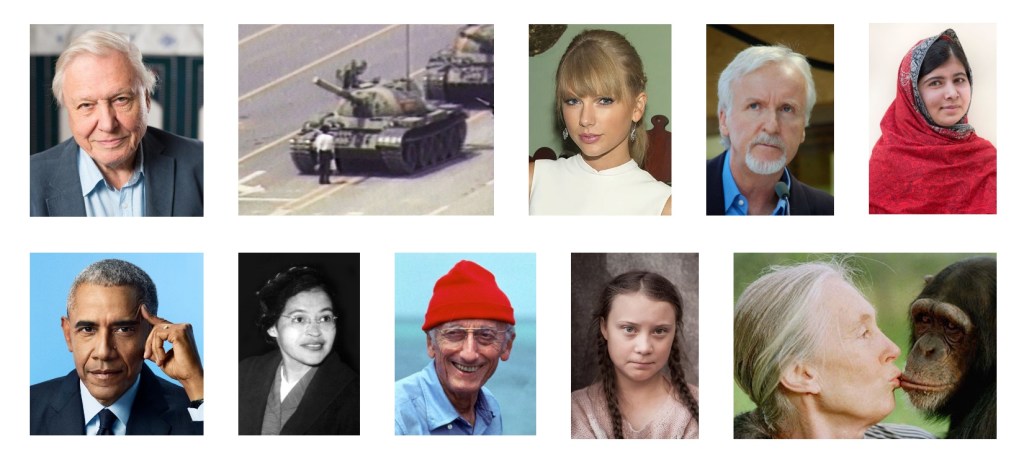

But it hasn’t always been good. I’ve spent time in countries ruled by totalitarian regimes, seeing how people who have no other choice must live, and feeling slightly embarrassed by the fact that I have the choice—the choice—not to live that way. In China, in Tiananmen Square, I was stopped by police and questioned aggressively for an hour because I was carrying a professional-looking camera. In that same country, I was told by the chipper hotel desk clerk when I checked in that I had to ‘register’ my laptop and mobile phone because, as a non-Chinese, I could be bringing in and distributing subversive materials that could be detrimental to the state. In Venezuela, my client would not allow me to go anywhere by myself, and assigned me a round-the-clock bodyguard to keep me out of trouble. In Yugoslavia, while driving in a car on the highway, I was frantically hushed by the other people in the car because they were afraid that my question about life under the current regime might be overheard by people outside the car. I listened and tried to understand the logic of a Russian man, who, when I took him (at his request) to a grocery store in California to see what it was like, stopped halfway down the coffee aisle, turned to me, and asked, “So many coffees! Why don’t they just pick the best one and give us that one?” It took me a few minutes to wrap my head around what he was really saying, and when I did, my hair stood on end. Why would I want they, whoever they is, picking my coffee? And in Africa and Australia, and frankly, parts of the American south, I watched as institutionalized racism turned my stomach. In Australia, I got into a cab, and soon after out of a cab, when the driver began spewing racial epithets and talking about the new Abo bars he had installed on his car. In Australia, many cars have pipe bumpers on the front that they call “Roo Bars,” referring to the fact that they are designed to keep kangaroos, when struck by the car, from damaging it. Abo bars refer to Aboriginal people—you understand why I got out of the cab. The man was a pig.

So you can imagine why I am hypersensitive to such behaviors, especially when I encounter them at home. There’s a lot to criticize about the United States. Racism, Sexism, and Ageism are alive and well in America, and by some estimations, once again getting worse. There is a growing income gap, driven by the overzealous forces of capitalism and manipulation of the rules by certain sectors of society, and it is tearing at the very fabric of national society. Educationally, we are in a tailspin, and the perceived value of education for the sake of education and its profound impact on the future of the country is at an all-time low. For all the rhetoric to the contrary, the skilled trades are still looked down on and often described as ‘what you do if you can’t get a real job.’ What short-sighted, hypocritical garbage. Education, in all its many forms, isn’t a barrier to progress; it’s a gateway that makes it possible.

Politically, we’ve never been more polarized. Some months ago, I had a conversation with a well-educated man—I emphasize that, well-educated—in the deep south, who took exception to something I said about the polarized nature of American politics. So, I invited him to have a conversation.

“What do you believe?” I asked him.

“I’m a Republican,” he replied.

“That’s not a belief—that’s a club you belong to,” I pushed back. He couldn’t get past that. So, I tried to make it easier.

“Look—I’m going to give you a series of questions; answer any one of them. Here we go: Tell me one thing that we could do in this country to fix the education system, or healthcare, or the economy, or infrastructure, or political gridlock, or the widening economic divide.”

He was unable to answer. But he reiterated his position as a Republican three times.

This is part of the problem. In the 60s and 70s, the chant that was often heard or seen on bumper stickers was, “My country, right or wrong.” Today, it seems to be, “My party, or my candidate, right or wrong.” And this is where I have a fundamental problem. ‘Country’ and ‘government’ are two very different different things that cannot and should not be conflated.

In the United States, we have a tricameral government to ensure checks and balances, to prevent one of the three from becoming more powerful than the other two. And, we have a two-party system, because they are ideologically different. One conservatively stresses small government, big business, and a culture of pulling yourself up by your bootstraps. I applaud that, when it’s possible.

The other party advocates for larger, more involved government, expanded social programs, and a more liberal approach to success. Interesting word, liberal. The dictionary defines it as ‘someone willing to respect or accept behavior or opinions different from their own, someone open to new ideas.’ And ‘someone’ can be an institution as much as it refers to an individual. The definition goes on to say that ‘liberal relates to or denotes a political and social philosophy that promotes individual rights, civil liberties, democracy, and free enterprise.’ By those definitions, every person in this country should proudly claim to be liberal, if we are committed as a nation to moving forward, not backward.

Somewhere in the territory between the ideologies of our political parties lies the fundamental essence of democratic freedom. Today, however, there is a massive, unfathomably wide gap between them, driven by political zealotry, greed, and government representatives who have forgotten that public service was never intended to be a career, an opportunity to feather one’s own nest. Government is not a business—and yet, based on the money that changes hands, and the extraordinary influence it wields over decisions that affect the governed, it is.

And yet: I support American Democracy, the so-called American Experiment, because I’ve seen the other side. I know what happens when totalitarianism is allowed to flourish, eroding individual freedoms, crushing the hope of women and minorities, destroying entire swaths of regional and national economies, stifling individual and organizational innovation, forcing businesses to flee to more open countries, slapping down the will of the people, and shuttering the media.

During Donald Trump’s first term, I wrote an essay in response to many of his actions which I ended with this statement:

I never express political arguments on a public forum, but for this, I make an exception. As someone who grew up in a country run by a dictator, and has traveled and worked in more than 100 countries, many of them run by despots and autocrats whose police harassed me because I carried a camera, required me to register my phone and laptop because I might engage in subversive activities, and suppressed the rights of their people to have a basic, fulfilling life and denied them a voice over their own destiny, I say ENOUGH. I can tolerate a lot, but this decision on Donald Trump’s part to ignore and openly criticize what we stand for as a free people and as a democratic nation goes far beyond ‘a misstep.’ This is not politically motivated on my part: I am motivated by indignation, anger, disappointment, and shame. I am tired of having to spend the first half-hour of every class I teach outside of this country, trying to explain the actions of this pompous fool who pretends to represent our country. ENOUGH. ENOUGH. ENOUGH.

That paragraph talks about what happens when totalitarianism and one-person rule are allowed to become the law of the land. It describes Russia, North Korea, China, Turkey, Venezuela, Myanmar, the Philippines, and others.

Now, cast an eye on the United States. Singlehanded, unilateral decisions, in the interests of big business, are swiping away vast swaths of public wild lands and National Park and Monument holdings. The current president and his appointees are giving a voice to extreme right-wing ultra-nationalists and white supremacists, destroying years of civil rights work. Women’s individual reproductive rights are being taken away, thanks to conservative appointments and ill-thought-out court decisions. News flash: a woman’s body is her and hers alone to govern, and governments cannot and should not legislate morality. That model is already taken: It’s called Saudi Arabia, Iran, Iraq, Afghanistan.

And what of the incipient trade wars looming on the horizon? Yes, there may be reasons to engage in tough conversations with our economic allies about trade imbalances, but waging a tariff-based trade war is not the answer. Here’s what we know from economic history that goes back to 15th-century China, when they were the dominant economic force on the planet. Global competition keeps the price of many goods down, which is good for everybody—and which is severely impacted in a tariff war. Free trade allows access to a wide range of services and goods, which tariffs diminish. Many of the gains of protectionism are short-lived and counter-productive; in fact, periods of protectionism have a historical habit of ending in economic downturn, most notably the Great Depression of the 1930s.

Closer to home, and more relevant in today’s world, when trade barriers go up, jobs that rely on the Internet disappear, as the barriers to the free movement of capital and labor get higher. Companies that are protected from outside competition may flourish in the short term, but are invariably less efficient in the longer term.

Truth: The only winning move is not to play.

Not long ago, I was in Northern California and southeastern Oregon, and I got into a conversation with a farmer who runs an enormous operation—thousands and thousands of acres. I asked him how things were going, given the talk of tariffs and such. He told me that tariffs were the least of his concerns, although they were concerns. His biggest issue was that his entire workforce had disappeared, because of fears of immigration coming down on them. And, all thoughts to the contrary, he couldn’t find local people willing to do the work that his previously Hispanic workforce was willing to do. He told me that he was down 80% of his staff, and that that was common across all the farms in the area. His solution? “Easy,” he told me. “Since Trump’s immigration policies have made my workforce disappear, I can’t operate my farm. So, I’m moving my farm to Mexico. The country is giving me tax breaks, so it’s a great deal.”

Great deal indeed. If the workers can’t come to the farm, the farm goes to the workers. And, of course, any products shipped out of Mexico to the United States will be classified as agricultural imports, and will therefore be taxed at a higher rate—which means higher prices at the grocery store. Very smart.

Finally, I have to speak out on behalf of the Press. I believe fervently that the single most important Freedom listed in the Bill of Rights is the first one: ‘Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.’ One thing that makes our system of government as good as it is, is that the press has the right, the obligation, and the responsibility to question government at every turn. That’s its job. When I hear our current president taking potshots at the Fifth Estate, it chills my blood. If you don’t want the press questioning your actions, then don’t engage in controversial actions that attract their attention. And by the way, be happy that you live in a country where the press has the right to do precisely that—and doesn’t serve as a marketing arm of the government. Again: that’s called Iran, or Russia, or North Korea, or Yemen, or Albania. Are those the countries we want to be lumped in with? The free Press serves as our collective societal conscience, and today we need it more than ever.

So yes—our government is not perfect, by any measure. It has warts, ugly parts, and is prone to mistakes. But it also has an obligation and responsibility to ultimately do the right thing for the people of this country. Go back to those opening lines:

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness. — That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed. From the consent of the governed—not the other way around.

This is not about blame: it’s about responsibility. It is not a partisan issue; it is a People of the United States issue, and ‘people’ includes those that we, the governed, place in office to serve us—not the other way around. As I told one person who commented on a different but related post, this challenge is not political—it’s genital. It’s time for the people of this country to grow a set, put on our big boy pants, and do the hard work of being responsible by reminding Washington, through our voices and actions at the polls, that this country is better than its government, and that the government serves the will of the people. I’ve spent too much of my life seeing firsthand what the alternative looks like in less-privileged countries: we must not and will not allow despotism or nationalism to define who we are. We’re better than that.

I close with this. Not long ago I read Brené Brown’s book, Braving the Wilderness. In it, she suggests four actions that would go a long way toward helping us get through this dysfunctional, angry, blame-ridden period.

People are hard to hate close up. Move in.

Speak truth to bullshit. Be civil.

Hold hands. With strangers.

Strong back. Soft front. Wild heart.

Those four statements are profound, and they define, as clearly as anything I’ve ever read, the soul of America. It’s time to get back to that, to the Shining City on the Hill, the model of strength, kindness, reason, and diplomacy that much of the world has historically held up as the model of global decorum. Washington, grow the hell up and start acting like there are grownups in the room. Politicians, from both sides, start doing your damn jobs, the ones you were elected to do. You might want to keep in mind the words of US Supreme Court Justice Robert Jackson, who in 1950 said, “It is not the function of our government to keep the citizen from falling into error; it is the function of the citizen to keep the government from falling into error.” And citizens? Enough with the doom-speak; enough with the hand-wringing. Speak up, think, be curious, and act. It is your right, and it is your responsibility. We owe this to our children, and we owe this to the world.

This is life. There is no easy button, and there never has been. It’s time we stopped looking for one.