Not long ago, I started doing something I always said I would do, but honestly never thought I’d actually get around to doing. Remember when you were in high school or college and your English teacher assigned you a book to read? And it wasn’t something fun like Hardy Boys or Tom Swift or Doc Savage (showing my age, here) or Little House on the Prairie. No, it was something BORING by Mark Twain or Charles Dickens or John Steinbeck. If you were like me, you faked it badly, or in college you might have run down to the bookstore to buy the summary of the book to make your fake a bit more believable. Either way, it rarely ended well.

I’m a writer and storyteller by trade—it’s who I am. And, because I’m a writer, I’m also an avid reader—and I mean, avid. I average about 140 books a year. So, a couple of years or so ago, I decided to start mixing the classics into my normal mix of books, starting with Arthur Conan Doyle. At first, I was dreading it. But once I started reading and allowed myself to slow my mind and my reading cadence to match the pace of 19th-century writers, I was hooked with the first book. I blazed through them all, the entire Sherlock Holmes collection, and then moved on to Jules Verne and Mark Twain and H.G. Wells. Reading those books as an adult, with the benefit of a bit more life behind me, gave the stories the context that was missing when I was a kid.

By the way, I have to interrupt myself here to tell you a funny story. I’m a pretty fast reader—not speed-reading fast, but fast. I pretty much keep the same reading cadence in every book I read, unless I’m reading poetry or a book by someone whose work demands a slower pace. Some southern writers, like Rick Bragg, slow me down, but in an enjoyable way. But a typical book of two or three-hundred pages or so, I usually blast through in about three days.

Not long ago, I read David Attenborough’s First Life, a book about the earliest organisms on the planet. That book took me two weeks to read. And it wasn’t because I wasn’t regularly reading it, or because the book was complicated, or poetic. It was because David Attenborough is one of those wonderful writers who writes the way he speaks. Which means that as I was reading, I was hearing his voice, and my reading began to mimic the pace at which he speaks on all the BBC programs: These … extraordinary creatures … equipped … as they are … for life in the shallow, salty seas … of the Pre-Cambrian world … quickly became the hunted … as larger … more complex creatures … emerged … on the scene.

I just couldn’t do it. I tried to read at a normal clip, and I stumbled and tripped over the words. It was pretty funny. It was also a great book.

Anyway, I just finished The Time Machine by H. G. Wells. I saw the movie as a kid, loved it, but the book was, as usual, quite different from the movie. I loved Wells’ writing, and it made me want to read more. So, I decided to read one of his lesser-known works, his Outline of History, a massive work of about 700 pages. And, as so often happens when I read something new, I had an epiphany.

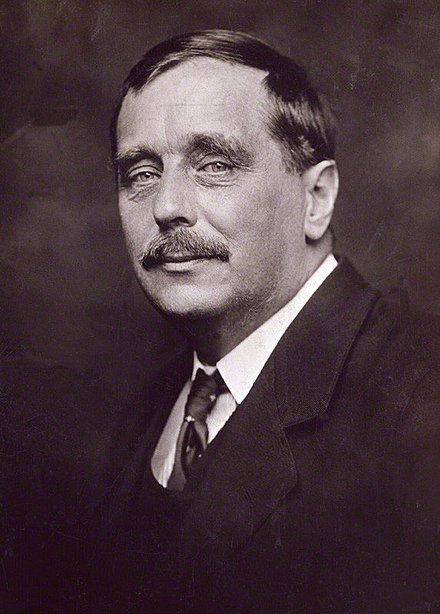

Let me tell you a bit about Herbert George Wells. During the 1930s, he was one of the most famous people in the world. He was a novelist and a Hollywood star, because several of his movies—The Invisible Man, Things to Come, and The Man Who Could Work Miracles were made into movies (the Time Machine didn’t hit the screens until later). In 1938, Orson Wells reportedly caused mass panic when he broadcast a radio show based on Well’s War of the Worlds, which also added to his fame. That story has since been debunked, but it did cause alarm among many.

Wells studied biology under T.H. Huxley at the UK’s Royal College of Science. He was a teacher and science writer before he was a novelist. Huxley, who served as a mentor for Wells, was an English biologist who specialized in comparative anatomy, but he was best known as “Darwin’s Bulldog” because of his loud support for Darwin’s theory of evolution. He also came up with the term, ‘agnosticism.’ “Agnosticism,” he described, “is not a creed, but a method, the essence of which lies in the rigorous application of a single principle… the fundamental axiom of modern science… In matters of the intellect, follow your reason as far as it will take you, without regard to any other consideration… In matters of the intellect, do not pretend that conclusions are certain which are not demonstrated or demonstrable.” Pretty prescient words that need to be broadcast loudly today. Ask questions, and don’t accept a statement as truth until you know it is. That’s precisely why I started this series.

Sorry—I’m all over the place here. The Outline of History tells the story of humankind from the earliest days of civilization to the end of World War I—The Great War, The War to End All Wars. If only.

From there, I went on to read Work, Wealth, and Happiness of Mankind, another of his lesser known works. Both are interesting takes on history and sociology, and somewhere between them, Wells invents the World Wide Web. Really.

Here’s how he begins the concept:

Before the present writer lie half a dozen books, and there are good indexes to three of them. He can pick up any one of these six books, refer quickly to a statement, verify a quotation, and go on writing. … Close at hand are two encyclopedias, a biographical dictionary, and other books of reference.

As a writer, Wells always had reference books on his desk that he used regularly. As he developed the concept that he came to call the World Brain, he wrote about the early scholars who lived during the time of the Library of Alexandria, the greatest center of learning and scholarship in the world at the time. It operated from the third century BC until 30 AD, an incredibly long time. Scholars could visit the Library, but they couldn’t take notes (there was no Paper), and there were no indices or cross-references between documents. So, Wells came up with the idea of taking information to the people instead of the other way around, and figuring out a way to create detailed cross-references—in effect, search capability—to make the vast stores of the world’s knowledge available, on demand, to everybody.

His idea was that the World Brain would be a single source of all of the knowledge contained in the world’s libraries, museums, and universities. He even came up with a system of classification, an information taxonomy, for all that knowledge.

Sometime around 1937, with the War to End All Wars safely in the past, Wells began to realize that the world was once again on the brink of conflict. To his well-read and research-oriented mind, the reason was sheer ignorance: people were really (to steal a word from my daughter) sheeple, and because they were ignorant and chose to do nothing about that, they allowed themselves to be fooled into voting for nationalist, fascist governments. The World Brain, he figured, could solve this problem, by putting all the world’s knowledge into the hands of all its citizens, thus making them aware of what they should do to preserve the peace that they had fought so hard to achieve less than twenty years earlier. What he DIDN’T count on, of course, was that he was dealing with people—and the fact that you can lead a horse to water, but you can’t make him drink from the intelligence well.

Nevertheless, he tried to raise the half million pounds a year that he felt would be needed to run the project. He wrote about it, gave lectures, toured the United States, and had dinner with President Roosevelt, during which he discussed the World Brain idea. He even met with scientists from Kodak who showed him their newest technology—the technology that ultimately became microfiche. But sadly, he couldn’t make it happen, and sure enough, World War II arrived.

Here’s how he summed up the value of the World Brain:

The general public has still to realize how much has been done in this field and how many competent and disinterested men and women are giving themselves to this task. The time is close at hand when any student, in any part of the world, will be able to sit with his projector in his own study at his or her own convenience to examine any book, any document, in an exact replica.

In other words…the World Wide Web. Imagine that.

World War II caused Wells to fall into a deep depression, during which he wrote The Time Machine, which is, I think, the first post-apocalyptic novel ever written—at least as far as I know. He describes the great green structure on the hill, made of beautiful porcelain but now falling down in ruins; I suspect he was thinking about the sacking and burning of the great Library of Alexandria when he wrote that part of the book.

Or, perhaps he was thinking of Percy Bysshe Shelley’s “Ozymandias”:

I met a traveller from an antique land,

Who said—“Two vast and trunkless legs of stone

Stand in the desert. . . . Near them, on the sand,

Half sunk a shattered visage lies, whose frown,

And wrinkled lip, and sneer of cold command,

Tell that its sculptor well those passions read

Which yet survive, stamped on these lifeless things,

The hand that mocked them, and the heart that fed;

And on the pedestal, these words appear:

My name is Ozymandias, King of Kings;

Look on my Works, ye Mighty, and despair!

Nothing beside remains. Round the decay

Of that colossal Wreck, boundless and bare

The lone and level sands stretch far away.”

Never underestimate the power of great literature. And never underestimate the power of curiosity when it’s unleashed on a problem.