As many of you know, I released a new novel not long ago called Russet. It’s my fourth work of fiction; all my prior titles (all 90+ of them) have been about technology, history, photography, writing, sound recording, storytelling, leadership, biography, and a few other genres. Anyway, Russet’s doing well, especially given the fact that I haven’t done much since its release to market or promote it. It’s my first science fiction book, and I had a blast writing it.

Ever since Russet hit the shelves, I’ve been getting an unusual number of emails and messages from people, asking me about writing books. Actually, they’re asking more than that. Many feel that they have a book inside themselves begging to be written, and want to know how to get it from mind to paper. Or, they have an idea that they think would make a good book, but don’t know how to bridge the gap between their idea and a finished work.

Well, I’ve thought about these questions, because they intrigue me, too. When I started out as a writer, I asked for and was kindly given advice by a handful of established journalists, feature writers, and novelists, and as my skill developed over the years I also learned from the soul-sucking and dehumanizing process of iterative manuscript submission, and the inevitable accumulation of an impressive collection of rejection letters. It’s painful, but it’s a necessary part of the writing and publishing process. It’s also educational.

So, after thinking about these questions, and about my own experiences as a professional writer, I think I have some additional wisdom to impart—at least I hope so. So here goes.

First, to the question of how to write a book. Writers are wired, you see, to believe, to conclude, that the story they want to share should be in the form of a book. And while that MAY be the best way to present a particular story, it’s not the ONLY one. Here’s an example.

In 1987 (yep, you read that correctly—almost 38 years ago!) I started writing a book called Whatever Happened to Mister Duncan, a collection of essays about childhood games and activities that were mostly played outside and that didn’t require anything other than our imaginations to play—okay, some of them required a pocket knife or a Popsicle stick, maybe a roll of caps and a rock, but that was pretty much it. No batteries, no screens, no keyboard or joystick. I had a hard time finishing the book; along the way I interviewed hundreds, maybe thousands, of people, asking them about their own childhood memories and what their favorite games and activities were. I then sat down and designed the book, laying out the logical sections which became chapters. But every time I thought I’d finished it, I’d get a call from somebody who wanted to share a long-forgotten memory, or a toy, or an experience that was so rich that it had to be in the book. So, I’d go back and do yet another rewrite. Because they were right—it HAD to be in the book.

The point at which I finally called a halt to the process was the 318th complete rewrite of the book. Yes, that’s a real number. I ended it by adding a paragraph that acknowledges the fact that the book will never actually be finished, but that I’ll include new material in a later edition.

So: 319 versions, by the time I finally had a complete, polished, nine-chapter, fully illustrated, 300-some-odd page book manuscript.

Which I have now decided should not be a book at all—at least, not exclusively.

This is a book about childhood. It’s experiential. I want it to evoke poignant memories of the period in our lives that caused us to become who we all are, before we had to start the odious task of adulting. You see, during those 38 years between the time that I first got the idea to write the book and when it finally emerged from its literary chrysalis, I did, as I said, hundreds of interviews; collected at least that many sound effects; and watched dozens and dozens of adults revert to childhood for the briefest periods during our conversations to show me something, before reverting back to boring, predictable, well-behaved adults. In other words, Duncan (my shorthand title for Whatever Happened to Mister Duncan) is a multiple media experience of sounds and different voices, none of which can adequately be presented between the pages of a book. Sure, I can transcribe the interviews, and I probably will, eventually, but what’s more fun: me writing down a list of all the different kinds of marbles that are out there, or listening to people struggle to remember the names of marbles as they dredge the murky depths of their own childhood memories? (Go ahead—I know you want to. Answer the question: how many marbles can YOU name?)

So: the decision was easy. This has to be an audio book.

NOT TOO LONG AGO, I took stock of the activities that give me pleasure, beyond the obvious ones—family, chasing grandkids, recording the sounds of the natural world. I love to write; I love to interview people so that I can learn about them and then tell their story on my Podcast; I love to teach; I love photography; and I love field recording. When I analyze all of those, I find that they all have one thing in common: they’re all different ways to tell stories. I’m a storyteller—plain and simple. I don’t write to publish a book; I write to tell a story. Here’s a little secret for you: I only publish about 30 percent of what I write. And what I mean by that is that I only TRY to publish about 30 percent. The rest? It’s for me, and the people I share it with.

Stories. Always, stories. It’s what people want to hear; it’s what gets them to focus; and it’s what has to be wrapped around facts if those facts are to be absorbed and retained. No story? No context. No context? No understanding. It’s that simple.

So, Duncan: I’ve decided to give it away, because the material is too good, too precious, too human to sell. It belongs to everybody, which is why it will soon emerge as a nine-chapter audio book as a gift to my listeners on the Natural Curiosity Project. I think you’ll like it—I really do. And check it out: just like that, my creative project is published. Who cares if I published it myself? The joy comes from sharing it, and engaging with those who choose to write or call me about it.

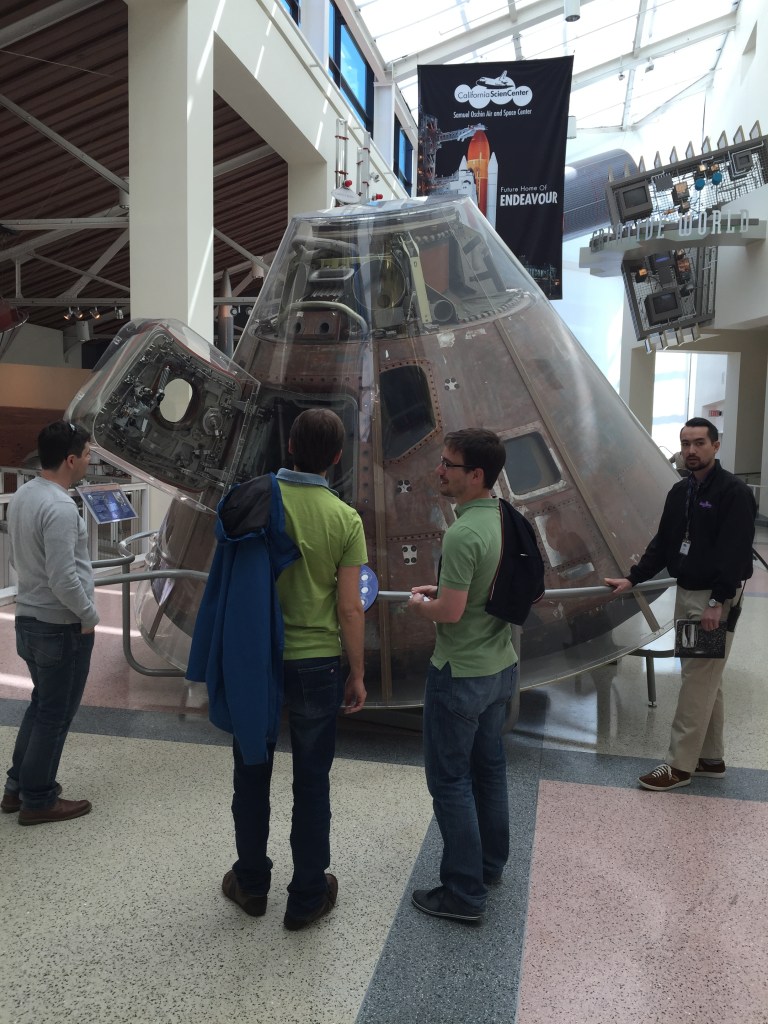

I USED TO RUN LEADERSHIP PROGRAMS at the University of Southern California’s Marshall School of Business. Some of them were multi-week programs, which meant that I’d often be in LA over a weekend. Well, one weekend I had nothing to do, so I walked over to a local science museum because it was only a couple of blocks away and I love museums. I’d never been to this one.

The place was pretty cool: outside, on stands, like gigantic versions of the model airplanes I built when I was a kid, they had an F-104 Starfighter and an SR-71, both amazing aircraft. Inside they had a whole collection of satellites, along with the usual kid-oriented science displays. As I explored the place, I found myself walking down a hall between exhibits, and as I passed a doorway, I looked into a dimly-lit room, and there, lined up in front of me, were a Mercury, a Gemini, and an Apollo capsule. Well, I’m a space geek, so I spent the next hour just walking around these things, peering inside, marveling at how—primitive they were. I kid you not, the seat the Mercury astronauts had to sit in was basically a lawn chair, made out of a metal pipe frame and braided leather straps. And based on the space inside, the astronauts couldn’t have been more than four feet tall. Gemini was no better. I’m exaggerating, but not by much. And Apollo? Bigger, but they also stuffed three people in there for the trip to the Moon. Here are the facts, according to NASA. The average length of a Mercury flight was 15 minutes. Gemini flights ranged from a few hours to one extreme endurance mission that lasted 14 days, But the average was three days. Apollo missions lasted an average of just over eight days.

Let me interrupt myself with another story before finishing this one. As I was standing there, admiring these early space capsules, I realized how dark it was in the room. So, I looked up at the ceiling to see the lights. Except I couldn’t see the lights. Why? Well, because just over my head, between me and the ceiling, was the gigantic delta wing of the Space Shuttle Endeavor. The one that they pulled down the streets of LA to get it there. It was so massive and took up so much space in the room that I didn’t notice it, I was so focused on those little capsules hiding in the shadows underneath it.

Yep—tears. Geek tears.

WHICH BRINGS ME TO THE SUBJECT OF ADVERBS. You remember—who, what, when, where, how, why. As a writer, adverbs are the best friend you can have.

My curiosity kicked in. There I was, in awe of the mighty space shuttle looking over me, looking at those capsules, thinking about how brave or crazy a person had to be to be bolted into one of those things, and how crowded it was, and how the Apollo astronauts basically just sat there in a space about the size of a VW Beetle for four days, one way, before turning around and doing it again in reverse. There was no bathroom, no privacy, no way to really get up and move around. Just shoot me now.

And that got me thinking—and here’s where the adverbs kicked in. A trip to Mars is somewhere between four-and-a-half and six months, depending on timing. How in the world could we possibly convince a crew to crawl into a ship for a journey that long? Why would they be willing to do it? How would we physically get them there? And thus was born the germ of an idea, the spark of a story, that led to all 625 pages of Russet. Because I figured it out—at least, I figured out ONE way. And I must be pretty accurate, because I got a call from a friend who works at our vaunted space agency, asking me after reading my book whether I had hacked their firewall (I didn’t). Gotta love that. Anyway, that’s how Russet got its start. It was all about the power of adverbs, especially how and why. Those two little words define curiosity. And when curiosity and storytelling are combined? Wow.

Acclaimed author Dorothy Parker once wrote that curiosity is the cure for boredom, but that there is no cure for curiosity. Thank goodness. Curiosity is what keeps the world moving forward. Would you like to see the Dark Ages again, the period that Bill Bryson describes in his book, The Mother Tongue: English and How It Got That Way, as “A period when history blends with myth and proof grows scant”? It’s easy: stop being curious. Does Bryson’s description of the Dark Ages sound alarming, given current events? Does it strike a bit close to home? Good. Get out there. Be curious. Share ideas. And don’t just blindly trust what you read or hear. Wield those adverbs. Question everything. It should be the law. Oh wait—it IS the law. It’s why we have a free press. My bad.