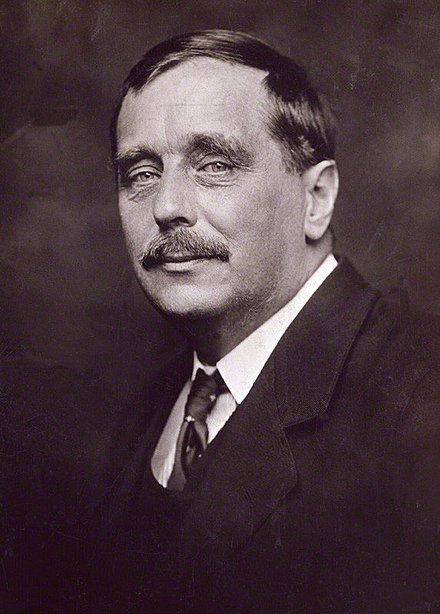

One of my favorite writers is an obscure guy that most people have never heard of. His name is Loren Eiseley, and he was a physical anthropologist and paleontologist at the University of Pennsylvania for over 30 years. As a young man, during the Great Depression, he was a ‘professional hobo,’ riding freight trains all over the United States, looking for work and the occasional adventure; his academic career came later. I’ve met few people who have read his books, yet few writers have affected me as much as he has.

Loren Eiseley in his office at the University of Pennsylvania Museum, May 12, 1960. Photo by Bernie Cleff, courtesy of the University of Pennsylvania Archives and Records Center.

I discovered Loren Eiseley when I was at Berkeley; a friend loaned me his book, All the Strange Hours: The Excavation of a Life. It’s mostly an autobiography, but it’s powerfully insightful about the world at large. He draws on his early experiences as a vagabond as much as he does as an academic, both of which yield a remarkable way of looking at the ancient and modern worlds.

I have all of his books, in both physical and ebook formats, and they’re among the few I never delete. I keep a list of quotes from Loren’s works in my phone, and I pull them up and read them every once in a while. Here are a few of my favorites. Remember, this guy is a hardcore scientist, although you’d never know it from what you’re about to read.

If there is magic on this planet, it is contained in water.

One does not meet oneself until one catches their reflection from an eye that is other than human.

The journey is difficult, immense. We will travel as far as we can, but we cannot in one lifetime see all that we would like to see or to learn all that we hunger to know.

If it should turn out that we have mishandled our own lives as several civilizations before us have done, it seems a pity that we should involve the violet and the tree frog in our departure.

When man becomes greater than nature, nature, which gave us birth, will respond. This last one strikes me as particularly prescient.

Ray Bradbury, another of my all-time favorite writers, said that ‘Eiseley is every writer’s writer, and every human’s human. He’s one of us, yet most uncommon.’

More than anything else, Loren Eiseley was a gifted observer and storyteller. In All the Strange Hours, he writes about a chance encounter on a train. I’d like to share a bit of it with you.

“In the fall of 1936 I belatedly entered a crowded coach in New York. The train was an early-morning express to Philadelphia and what I had been doing in New York the previous day I no longer remember. The crowded car I do remember because there was only one seat left, and it was clearly evident why everyone who had boarded before me had chosen to sit elsewhere.The vacant seat was beside a huge and powerful man who seemed slumped in a drunken stupor. I was tired, I had once lived amongst rough company, and I had no intention of standing timidly in the aisle. The man did not look quarrelsome, just asleep. I sat down and minded my own business.

Eventually the conductor made his way down the length of the coach to our seats. I proceeded to yield up my ticket. Just as I was expecting the giant on my right to be nudged awake, he straightened up, whipped out his ticket and took on a sharp alertness, so sharp in fact, that I immediately developed the uncanny feeling that he been holding that particular seat with a show of false drunkenness until the right party had taken it. When the conductor was gone, the big man turned to me with the glimmer of amusement in his eyes. “Stranger,” he appealed before I could return to my book, “tell me a story.” In all the years since, I have never once been addressed by that westernism “stranger” on a New York train. And never again upon the Pennsylvania Railroad has anyone asked me, like a pleading child, for a story. The man’s eyes were a deep fathomless blue with the serenity that only enormous physical power can give. People on trains out of New York tend to hide in their own thoughts. With this man it was impossible. I smiled back at him. ‘You look at me,’ I said, running an eye over his powerful frame, ‘as if you were the one to be telling me a story. I’m just an ordinary guy, but you, you look as if you have been places. Where did you get that double thumb?’

With the eye of a physical anthropologist, I had been drawn to some other characters than just his amazing body. He held up a great fist, looking upon it contemplatively as though for the first time.”

That’s just GREAT writing. Powerfully insightful, visual, and entertaining. And, it demonstrates Eiseley’s skill as a naturally curious storyteller, and the use of storytelling as an engagement technique. His willingness to talk with the odd guy in the next seat over, to ask questions, to give the guy the opportunity to talk, demonstrates one of the most important powers of storytelling.

For most people, storytelling is a way to convey information to another person, or to a group. And while that’s certainly true, that’s not the most important gift of storytelling. The best reason to tell stories is to compel the other person to tell a story BACK. Think about the last time you were sitting with a group of friends, maybe sharing a glass of wine. People relax and get comfortable, and the stories begin. One person tells a story, while everyone else listens. When they finish, someone else responds: ‘Wow. That reminds me of the time that…’ and so it goes, around the group, with everyone sharing.

When this happens, when the other person starts talking, this is your opportunity to STOP talking and listen—to really listen to the person. They’re sharing something personal with you, something that’s important and meaningful to them—which means that it should be important and meaningful to you, if you want to have any kind of relationship with that person. It’s a gift, so treat it accordingly.

In west Texas, there’s an old expression that says, ‘Never miss a good chance to shut up.’ This is one of those times. By letting his seat mate talk, Loren Eiseley discovered amazing insights about him, but not just about him. He also learned about his views of society and the world. The conversation goes on for many pages beyond what I quoted earlier, and it’s powerful stuff. So never underestimate the power of the story as an insight gathering mechanism, as much as it is an opportunity to share what YOU have to say.

Here’s one last thing I want to mention. In the tenth episode of my Podcast, The Natural Curiosity Project, I talked about a book I had recently read called ‘The Age of Wonder.’ It’s the story of the scientists of the Romantic Age (1798-1837) who made some of the most important discoveries of the time—people like Charles Babbage, William Herschel, Humphrey Davy, Michael Faraday, and Mungo Park, scientists who had one thing in common: their best friends, partners, and spouses were, without exception, artists—poets and novelists, for the most part.

These were serious, mainstream, well-respected scientists. For example, Charles Babbage was a mathematician who was the father of modern computing (he invented the Difference Engine, a mechanical calculator that had more than 25,000 brass gears). He was married to Ada Lovelace, the daughter of the poet Lord Byron, and a writer and mathematician herself. William Hershel built the world’s first very large telescopes in England, and his best friend was George Gordon, better known as Lord Byron, the romantic poet. Humphrey Davy was a chemist and anatomist who discovered the medicinal properties of nitrous oxide. His closest friend was the poet and essayist Samuel Taylor Coleridge, who wrote Kubla Khan and The Rime of the Ancient Mariner.

In Xanadu did Kubla Khan,

A stately pleasure-dome decree:

Where Alph, the sacred river, ran,

Through caverns measureless to man,

Down to a sunless sea.

John Keats, a poet and the author of Ode on a Grecian Urn, was also a medical student whose scientific pursuits shaped his poetry. Mary Shelley is well known as the author of Frankenstein; her last name is Shelley because she was married to Percy Bysshe Shelley, another romantic poet and essayist:

I met a traveller from an antique land,

Who said—“Two vast and trunkless legs of stone

Stand in the desert. . . . Near them, on the sand,

Half sunk a shattered visage lies, whose frown,

And wrinkled lip, and sneer of cold command,

Tell that its sculptor well those passions read

Which yet survive, stamped on these lifeless things,

The hand that mocked them, and the heart that fed;

And on the pedestal, these words appear:

My name is Ozymandias, King of Kings;

Look on my Works, ye Mighty, and despair!

Shelley’s work was filled with and flavored by the wonders of science.

So, you may be wondering if there’s a ‘so what’ coming any time soon. The answer is yes: Don’t you find it interesting that these scientists were all supported by and influenced by their artistic friends, and vice-versa? What does that tell us about the importance of the linkage between science and the arts? Well, there’s a huge focus right now in schools on STEM—Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math. Now look: I’ll be the first to tell you that those are all important, but there’s are two letters missing: it should be STREAM. The ‘R’ is for ‘Reading,’ a necessary and critical skill, and the ‘A’ for ‘Arts’ needs to be in there as well, with as much emphasis and priority as the others. Anyone who doubts that should look to the lessons of earlier history.

And Loren Eiseley—remember him? Where does he fit into this? Well, think about it. What made him such a gifted scientist was the fact that he was, in addition to being a respected scientist, a gifted essayist and poet. During his life he wrote nine books, hundreds of essays, and several collections of poetry, all centered on the wonders of the natural world. His philosophy, his approach to his profession, embodied the learnings from the Age of Wonder.

In one of his essays, ‘How Flowers Changed the World’ (which you’ll find in his book, ‘The Immense Journey’), Loren Eiseley had this to say:

If our whole lives had not been spent in the midst of it, the natural world would astound us. The old, stiff, sky-reaching wooden world (he’s talking about trees here) changed into something that glowed here and there with strange colors, put out queer, unheard of fruits and little intricately carved seed cases, and, most important of all, produced concentrated foods in a way that the land had never seen before, or dreamed of back in the fish-eating, leaf-crunching days of the dinosaurs.”

Imagining the first human being who pondered the possibility of planting seeds, he writes: “In that moment, the golden towers of man, his swarming millions, his turning wheels, the vast learning of his packed libraries, would glimmer dimly there in the ancestor of wheat, a few seeds held in a muddy hand. Without the gift of flowers and the infinite diversity of their fruits, man and bird, if they had continued to exist at all, would be today unrecognizable.

Archaeopteryx, the lizard-bird, might still be snapping at beetles on a sequoia limb; man might still be a nocturnal insectivore gnawing a roach in the dark. The weight of a petal has changed the face of the world and made it ours.”

The poetic power of Loren’s science writing infuses the facts with human wonder. Here he is, writing about the stupefyingly boring topic of angiosperms, seeds that are enclosed in some kind of protective capsule, yet, we’re mesmerized by the imagery his words create.

What a world. And it’s ours.