*A note before you begin to read: This is a long post; if you’d rather listen to it, you can find it at the Natural Curiosity Project Podcast.

Part I

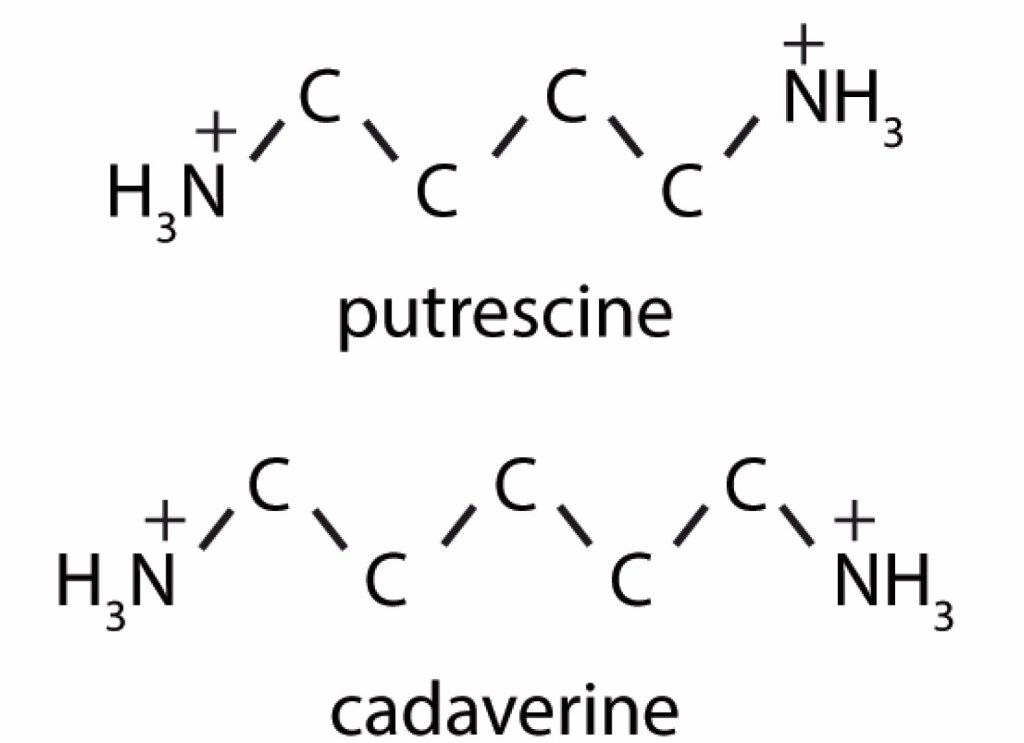

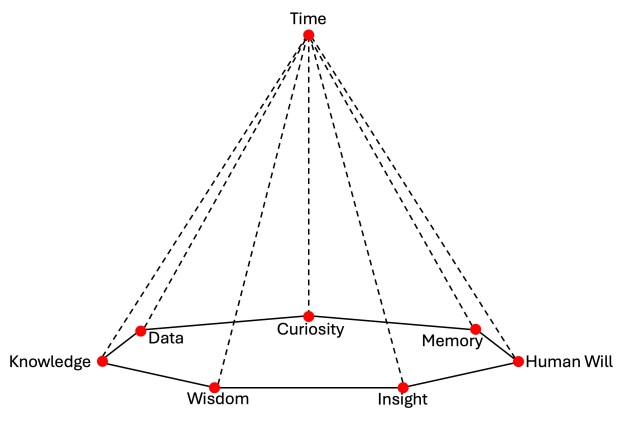

LIFE IS VISUAL, so I have an annoying tendency to illustrate everything—either literally, with a contrived graphic or photo, or through words. So: try to imagine a seven-sided polygon, the corners of which are labeled curiosity, knowledge, wisdom, insight, data, memory, and human will. Hovering over it, serving as a sort of conical apex, is time.

Why these eight words? A lifetime of living with them, I suppose. I’m a sucker for curiosity; it drives me, gives my life purpose, and gives me a decent framework for learning and applying what I learn. Knowledge, wisdom, insight, and data are ingredients that arise from curiosity and that create learning. Are they a continuum? Is one required before the next? I think so, but that could just be because of how I define the words. Data, to me, is raw ore, a dimensionless precursor. When analyzed, which means when I consider it from multiple perspectives and differing contexts, it can yield insight—it lets me see beyond the obvious. Insight, then, can become knowledge when applied to real-world challenges, and knowledge, when well cared for and spread across the continuum of a life of learning, becomes wisdom. And all of that yields learning. And memory? Well, keep listening.

Here’s how my model came together and why I wrestle with it.

Imagine an existence where our awareness of ‘the past’ does not exist, because our memory of any action disappears the instant that action takes place. In that world, a reality based on volatile memory, is ‘learning,’ perhaps defined as knowledge retention, possible? If every experience, every gathered bit of knowledge, disappears instantly, how do we create experience that leads to effective, wisdom-driven progress, to better responses the next time the same thing happens? Can there even be a next time in that odd scenario, or is everything that happens to us essentially happening for the first time, every time it happens?

Now, with that in mind, how do we define the act of learning? It’s more than just retention of critical data, the signals delivered via our five senses. If I burn myself by touching a hot stove, I learn not to do it again because I form and retain a cause-effect relationship between the hot stove, the act of touching it, and the pain the action creates. So, is ‘learning’ the process of applying retained memory that has been qualified in some way? After all, not all stoves are hot.

Sometime around 500 BC, the Greek playwright Aeschylus observed that “Memory is the mother of all wisdom.” If that’s the case, who are we if we have no memory? And I’m not just talking about ‘we’ as individuals. How about the retained memory of a group, a community, a society?

Is it our senses that give us the ability to create memory? If I have no senses, then I am not sentient. And if I am not sentient, then I can create no relationship with my environment, and therefore have no way to respond to that environment when it changes around me. And if that happens, am I actually alive? Is this what awareness is, comprehending a relationship between my sense-equipped self and the environment in which I exist? The biologist in me notes that even the simplest creatures on Earth, the single-celled Protozoa and Archaea, learn to respond predictably to differing stimuli.

But I will also observe that while single-celled organisms routinely ‘learn,’ many complex multi-celled organisms choose not to, even though they have the wherewithal to do so. Many of them currently live in Washington, DC. A lifetime of deliberate ignorance is a dangerous thing. Why, beyond the obvious? Because learning is a form of adaptation to a changing environment—call it a software update if you’re more comfortable with that. Would you sleep well at night, knowing that the antivirus software running on your computer is a version from 1988? I didn’t think so. So, why would you deliberately choose not to update your personal operating system, the one that runs in your head? This is a good time to heed the words of Charles Darwin: It is not the strongest that survive, nor the most intelligent, but those that are most adaptable to change. Homo sapiens, consider yourselves placed on-notice.

Part II

RELATED TO THIS CONUNDRUM IS EPISTEMOLOGY—the philosophy that wrestles with the limits of knowledge. Those limits don’t come about because we’re lazy; they come about because of physics.

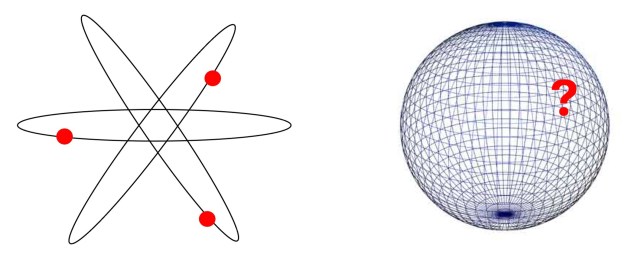

From the chemistry and physics I studied in college, I learned that the convenient, simple diagram of an atom that began to appear in the 1950s is a myth. Electrons don’t orbit the nucleus of the atom in precise paths, like the moon orbiting the Earth or the Earth orbiting the Sun. They orbit according to how much energy they have, based on their distance from the powerfully attractive nucleus. The closer they are, the stronger they’re held by the electromagnetic force that holds the universe together. But as atoms get bigger, as they add positively-charged protons and charge-less neutrons in the densely-packed nucleus, and layer upon layer of negatively charged orbiting electrons to balance the nuclear charge, an interesting thing happens. As layers of electrons are added, the strength with which the outermost electrons are held by the nucleus decreases with distance, making them less ‘sticky,’ and the element becomes less stable.

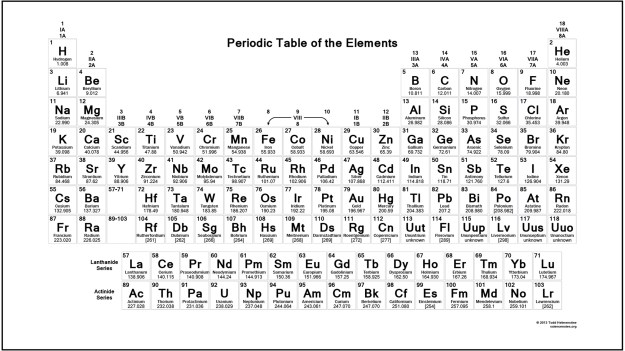

This might be a good time to make a visit to the Periodic Table of the Elements. Go pull up a copy and follow along.

Look over there in the bottom right corner. See all those elements with the strange names and big atomic numbers—Americium, Berkelium, Einsteinium, Lawrencium? Those are the so-called transuranium elements, and they’re not known for their stability. If a distant electron is attracted away for whatever reason, that leaves an element with an imbalance—a net positive charge. That’s an unstable ion with a positive charge that wants to get back to a stable state, a tendency defined by the Second Law of Thermodynamics and a process called entropy, which we’ll discuss shortly. It’s also the heart of the strange and wonderful field known as Quantum Mechanics.

This is not a lesson in chemistry or nuclear physics, but it’s important to know that those orbiting electrons are held within what physicists call orbitals, which are statistically-defined energy constructs. We know, from the work done by scientists like Werner Heisenberg, who was a physicist long before he became a drug dealer, that an electron, based on how far it is from the nucleus and therefore how much energy it has, lies somewhere within an orbital. The orbitals, which can take on a variety of three-dimensional shapes that range from a single sphere to multiple pear-shaped spaces to a cluster of balloons, define atomic energy levels and are stacked and interleaved so that they surround the nucleus. So, the orbital that’s closest to the nucleus is called the 1s orbital, and it’s shaped like a sphere. In the case of Hydrogen, element number one in the Periodic Table, somewhere within that orbital is a single lonely electron. We don’t know precisely where it is within the 1s orbital at any particular moment; we just know that it’s somewhere within that mathematically-defined sphere. This is what the Heisenberg Uncertainty Principle is all about: we have no way of knowing what the state of any given electron is at any point in time. And, we never will. We just know that statistically, it’s somewhere inside that spherical space.

Which brings us back to epistemology, the field of science (or is it philosophy?) that tells us that we can never know all that there is to know, that there are defined limits to human knowledge. Here’s an example. We know beyond a shadow of a doubt that the very act of observing the path of an electron changes the trajectory of that electron, which means that we can never know what its original trajectory was before we started observing it. This relationship is described in a complex mathematical formula called Schrödinger’s Equation.

Look it up, study it, there will be a test. The formula, which won its creator, Erwin Schrödinger, the Nobel Prize in 1933, details the statistical behavior of a particle within a defined space, like an energy-bound atomic orbital. It’s considered the fundamental principle of quantum mechanics, the family of physics that Albert Einstein made famous. In essence, we don’t know, we can’t know, what the state of a particle is at any given moment, which implies that the particle can exist, at least according to Schrödinger, in two different states, simultaneously. This truth lies at the heart of the new technology called quantum computing. In traditional computing, a bit (Binary Digit) can have one or the other of two states: zero or one. But in quantum computing, we leave bits behind and transact things using Qubits (quantum bits), which can be zero, one, or both zero and one at the same time. Smoke ‘em if you got ‘em.

The world isn’t neat and tidy where it matters: it’s sloppy and ill-defined and statistical. As much as the work of Sir Isaac Newton described a physical world defined by clear laws of gravity, and velocity, and acceleration, and processes that follow clearly-defined, predictably linear outcomes, Schrödinger’s, Heisenberg’s, and Einstein’s works say, not so fast. At the atomic level, the world doesn’t work that way.

I know—you’re lighting up those doobies as you read this. But this is the uncertainty, the necessary inviolable unknown that defines science. Let me say that again, because it’s important. Uncertainty Defines Science. It’s the way of the universe. Every scientific field of study that we put energy into, whether it’s chemistry, pharmacology, medicine, geology, engineering, genetics, or a host of others, is defined by the immutable Laws of Physics, which are governed by the necessary epistemological uncertainties laid down by people like Werner Heisenberg and Erwin Schrödinger, and codified by Albert Einstein.

Part III

ONE OF MY FAVORITE T-SHIRTS SAYS,

I READ.

I KNOW SHIT.

I’m no physicist, Not by a long shot. But I do read, I did take Physics and Chemistry, and I was lucky enough to have gone to Berkeley, where a lot of this Weird Science was pioneered. I took organic chemistry from a guy who was awarded a Nobel Prize and had more than a few elements named after him (Glenn Seaborg) and botany from the guy who discovered how photosynthesis works and also had a Nobel Prize (Melvin Calvin). I know shit.

But the most important thing I learned and continue to learn, thanks to those grand masters of knowledge, is that uncertainty governs everything. So today, when I hear people criticizing scientists and science for not being perfect, for sometimes being wrong, for not getting everything right all the time, for not having all the answers, my blood boils, because they’re right, but for the wrong reasons. Science is always wrong—and right. Schrödinger would be pleased with this duality. It’s governed by the same principles that govern everything else in the universe. Science, which includes chemistry, pharmacology, medicine, geology, engineering, genetics, and all the other fields that the wackadoodle pseudo-evangelists so viciously criticized during the pandemic, and now continue to attack, can’t possibly be right all the time because the laws of the universe fundamentally prevent us from knowing everything we need to know to make that happen. Physics doesn’t come to us in a bento box wrapped in a ribbon. Never in the history of science has it ever once claimed to be right. It has only maintained that tomorrow it will be more right than it is today, and even more right the day after that. That’s why scientists live and die by the scientific method, a process that aggressively and deliberately pokes and prods at every result, looking for weaknesses and discrepancies. Is it comfortable for the scientist whose work is being roughed up? Of course not. But it’s part of being a responsible scientist. The goal is not for the scientist to be right; the goal is for the science to be right. There’s a difference, and it matters.

This is science. The professionals who practice it, study it, probe it, spend their careers trying to understand the rules that govern it, don’t work in a world of absolutes that allow them to design buildings that won’t fail and drugs that will work one hundred percent of the time and to offer medical diagnoses that are always right and to predict violent weather with absolute certainty. No: they live and work in a fog of uncertainty, a fuzzy world that comes with no owner’s manual, yet with that truth before them, and accepting the fact that they can never know enough, they do miraculous things. They have taken us to the stars, created extraordinary energy sources, developed mind-numbingly complex genetic treatments and vaccines, and cured disease. They have created vast, seamless, globe-spanning communications systems, the first glimmer of artificial intelligence, and demonstrated beyond doubt that humans play a major role in the fact that our planet is getting warmer. They have identified the things that make us sick, and the things that keep us well. They have helped us define ourselves as a sentient species.

And, they are pilloried by large swaths of the population because they’re not one hundred percent right all the time, an unfair expectation placed on their shoulders by people who have no idea what the rules are under which they work on behalf of all of us.

Here’s the thing, for all of you naysayers and armchair critics and nonbelievers out there: Just because you haven’t taken the time to do a little reading to learn about the science behind the things that you so vociferously criticize and deny, just because you choose deliberate ignorance over an updated mind, doesn’t make the science wrong. It does, however, make you lazy and stupid. I know shit because I read. You don’t know shit because you don’t. Take a lesson from that.

Part IV

THIS ALSO TIES INTO WHAT I BELIEVE to be the most important statement ever uttered by a sentient creature, and it begins at the liminal edges of epistemological thought: I am—the breathtaking moment of self-awareness. Does that happen the instant a switch flips and our senses are activated? If epistemology defines the inviolable limits of human knowledge, then what lies beyond those limits? Is human knowledge impeded at some point by a hard-stop electric fence that prevents us from pushing past the limits? Is there a ‘there be dragons here’ sign on the other side of the fence, prohibiting us from going farther? I don’t think so. For some, that limit is the place where religion and faith take over the human psyche when the only thing that lies beyond our current knowledge is darkness. For others, it stands as a challenge: one more step moves us closer to…what, exactly?

A thinking person will experience a moment of elegance here, as they realize that there is no fundamental conflict between religious faith and hardcore science. The two can easily coexist without conflict. Why? Because uncertainty is alive and well in both. Arthur C. Clarke: Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.

Part V

THIS BRINGS ME TO TIME, and why it sits at the apex of my seven-sided cone. Does time as we know it only exist because of recallable human memory? Does our ability to conceive of the future only exist because, thanks to accessible memory and a perception of the difference between a beginning state and an end state, of where we are vs. where we were, we perceive the difference between past and present, and a recognition that the present is the past’s future, but also the future’s past?

Part VI

SPANISH-AMERICAN WRITER AND PHILOSOPHER George Santayana is famous for having observed that ‘those who fail to heed the lessons of history are doomed to repeat them.’ It’s a failing that humans are spectacularly good at, as evidenced by another of Santayana’s aphorisms—that ‘only the dead have seen the end of war.’ I would observe that in the case of the first quote, ‘heed’ means ‘to learn from,’ not simply ‘to notice.’ But history, by definition, means learning from things that took place in the past, which means that if there is no awareness of the past, then learning is not possible. So, history, memory, and learning are, to steal from Douglas Adams, the author of The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, “inextricably intertwingled” (more on that phrase later). And if learning can’t happen, does that then mean that time, as we define it, stops? Does it become dimensionless? Is a timeless system the ultimate form of entropy, the tendency of systems to seek the maximum possible state of disorder, including static knowledge? Time, it seems, implies order, a logical sequence of events that cannot be changed. So, does entropy seek timelessness? Professor Einstein, white courtesy telephone, please.

The Greek word chronos defines time as a physical constant, as in, I only have so much time to get this done. Time is money. Only so much time in a day. 60 seconds per minute, 60 minutes per hour, 24 hours per day. But the Greeks have a second word, kairós, which refers to the quality of time, of making the most of the time you have, of savoring time, of using it to great effect. Chronos, it seems, is a linear and quantitative view of time; kairós is a qualitative version.

When I was a young teenager, I read a lot of science fiction. One story I read, a four-book series by novelist James Blish (who, with his wife, wrote the first Star Trek stories for television), is the tale of Earth and its inhabitants in the far distant future. The planet’s natural resources have been depleted by human rapaciousness, so, entire cities lift off from Earth using a form of anti-gravity technology called a Gravity Polaritron Generator, or spindizzy for short, and become independent competing entities floating in space.

In addition to the spindizzy technology, the floating cities have something called a stasis field, within which time does not exist. If someone is in imminent danger, they activate a stasis field that surrounds them, and since time doesn’t exist within the field, whatever or whoever is in it cannot be hurt or changed in any way by forces outside the field. It’s an interesting concept, which brings me to a related topic.

One of my favorite animals, right up there with turtles and frogs, is the water bear, also called a tardigrade (and, charmingly by some, a moss piglet). They live in the microscopically tiny pools of water that collect on the dimpled surfaces of moss leaves, and when viewed under a microscope look for all the world like tiny living gummy bears.

Tardigrades can undergo what is known as cryptobiosis, a physiological process by which the animal can protect itself from extreme conditions that would quickly kill any other organism. Basically, they allow all the water in their tiny bodies to completely evaporate, in the process turning themselves into dry, lifeless little husks. They become cryptospores. Water bears have been exposed to the extreme heat of volcanos, the extreme cold of Antarctica, and intense nuclear radiation inside power plants; they have been placed outside on the front stoop of the International Space Station for days on end, then brought inside, with no apparent ill effects. Despite the research into their ability to survive such lethal environments, we still don’t really know how they do it. Uncertainty.

But maybe I do know. Perhaps they have their own little stasis field that they can turn on and off at will, in the process removing time as a factor in their lives. Time stops, and if life can’t exist without time, then they can’t be dead, can they? They become like Qubits, simultaneously zero and one, or like Schrödinger’s famous cat, simultaneously dead and alive.

Part VII

IN THE HITCHHIKER’S GUIDE TO THE GALAXY, Douglas Adams uses the phrase I mentioned earlier and that I long ago adopted as one of my teaching tropes. It’s a lovely phrase that just rolls off the tongue: “inextricably intertwingled.” It sounds like a wind chime when you say it out loud, and it makes audiences laugh when you use it to describe the interrelatedness of things.

The phrase has been on my mind the last few days, because its meaning keeps peeking out from behind the words of the various things I’ve been reading. Over the last seven days I’ve read a bunch of books from widely different genres—fiction, biography, science fiction, history, philosophy, nature essays, and a few others that are hard to put into definitive buckets.

There are common threads that run through all of the books I read, and not because I choose them as some kind of a confirmationally-biased reading list (how could Loren Eiseley’s Immense Journey, Arthur C. Clarke’s Songs of a Distant Earth, E. O. Wilson’s Tales from the Ant World, Malcolm Gladwell’s Revenge of the Tipping Point, Richard Feynman’s Surely You’re Joking, Mister Feynman, and Studs Terkel’s And They All Sang possibly be related, other than the fact that they’re books?). Nevertheless, I’m fascinated by how weirdly connected they are, despite being so very, very different. Clarke, for example, writes a whole essay in Songs of a Distant Earth about teleology, a term I’ve known forever but have never bothered to look up. It means looking at the cause of a phenomenon rather than its perceived purpose to discern its reason for occurring. For example, in the wilderness, lightning strikes routinely spark forest fires, which burn uncontrolled, in the process cleaning out undergrowth, reducing the large-scale fire hazard, but doing very little harm to the living trees, which are protected by their thick bark—unless they’re unhealthy, in which case they burn and fall, opening a hole in the canopy that allows sunlight to filter to the forest floor, feeding the seedlings that fight for their right to survive, leading to a healthier forest. So it would be easy to conclude that lightning exists to burn forests. But that’s a teleological conclusion that focuses on purpose rather than cause. Purpose implies intelligent design, which violates the scientific method because it’s subjective and speculative. Remember—there’s no owners manual.

The initial cause of lightning is wind. The vertical movement of wind that precedes a thunderstorm causes negatively charged particles to gather near the base of the cloud cover, and positively charged particles to gather near the top, creating an incalculably high energy differential between the two. But nature, as they say, abhors a vacuum, and one of the vacuums it detests is the accumulation of potential energy. Natural systems always seek a state of entropy—the lowest possible energy state, the highest state of disorder. I mentioned this earlier; it’s a physics thing, the Second Law of Thermodynamics. As the opposing charges in the cloud grow (and they are massive—anywhere from 10 to 300 million volts and up to 30,000 amps), their opposite states are inexorably drawn together, like opposing poles of a gigantic magnet (or the positively charged nuclei and negatively charged electrons of an atom), and two things can happen. The energy stored between the “poles” of this gigantic aerial magnet—or, if you prefer, battery—discharges within the cloud, causing what we sometimes call heat lightning, a ripple of intense energy that flashes across the sky. Or, the massive negative charge in the base of the cloud can be attracted to positive charges on the surface of the Earth—tall buildings, antenna towers, trees, the occasional unfortunate person—and lightning happens.

It’s a full-circle entropic event. When a tree is struck and a fire starts, the architectural order that has been painstakingly put into place in the forest by nature is rent asunder. Weaker trees fall, tearing open windows in the canopy that allow sunlight to strike the forest floor. Beetles and fungi and slugs and mosses and bacteria and nematodes and rotifers consume the fallen trees, rendering them to essential elements that return to the soil and feed the healthy mature trees and the seedlings that now sprout in the beams of sunlight that strike them. The seedlings grow toward the sunlight; older trees become unhealthy and fall; order returns. Nature is satisfied. Causation, not purpose. Physics, not intelligent design. Unless, of course, physics is intelligent design. But we don’t know. Uncertainty.

E. O. Wilson spends time in more than one of his books talking about the fact that individuals will typically act selfishly in a social construct, but that groups of individuals in a community will almost always act selflessly, doing what’s right for the group. That, by the way, is the difference between modern, unregulated capitalism and what botany professor Robin Wall Kimmerer calls “the gift economy” in her wonderful little book, The Serviceberry. This is not some left-leaning, unicorn and rainbows fantasy: it’s a system in which wealth is not hoarded by individuals, but rather invested in and shared with others in a quid pro quo fashion, strengthening the network of relationships that societies must have to survive and flourish. Kimmerer cites the story of an anthropologist working with a group of indigenous people who enjoy a particularly successful hunt, but is puzzled by the fact that they now have a great deal of meat but nowhere to keep it cold so that it won’t spoil. “Where will you store it to keep it fresh for later?” The anthropologist asks. “I store it in my friends’ bellies,” the man replies, equally puzzled by the question. This society is based on trust, on knowing that the shared meat will be repaid in kind. It is a social structure based on strong bonds—kind of like atoms. Bonds create stability; individual particles do the opposite, because they’re less stable.

In fact, that’s reflected in many of the science fiction titles I read: that society’s advances come about because of the application of the common abundance of human knowledge and will. Individuals acting alone rarely get ahead to any significant degree, and if they do, it’s because of an invisible army working behind them. But the society moves ahead as a collective whole, with each member contributing. Will there be those who don’t contribute? Of course. It’s a function of uncertainty and the fact that we can never know with one hundred percent assurance how an individual within a group will behave. There will always be outliers, but their selfish influence is always neutralized by the selfless focus of the group. The behavior of the outlier does not define the behavior of the group. ‘One for one and none for all’ has never been a rallying call.

Part VIII

THIS ESSAY APPEARS TO WANDER, because (1) it wanders and (2) it connects things that don’t seem to be connected at all, but that clearly want to be. Learning doesn’t happen when we focus on the things; it happens when we focus on the connections between the things. The things are data; the connections create insight, which leads to knowledge, wisdom, action, a vector for change. Vector—another physics term. It refers to a quantity that has both direction and magnitude. The most powerful vector of all? Curiosity.

Science is the only tool we have. It’s an imperfect tool, but it gets better every time we use it. Like it or not, we live in a world, in a universe, that is defined by uncertainty. Science is the tool that helps us bound that uncertainty, define its hazy distant edges, make the unclear more clear, every day. Science is the crucible in which human knowledge of all things is forged. It’s only when we embrace that uncertainty, when we accept it as the rule of all things, when we revel in it and allow ourselves to be awed by it—and by the science-based system that allows us to constantly push back the darkness—that we begin to understand. Understand what, you say? Well, that’s the ultimate question, isn’t it?