Dr. Steven Shepard

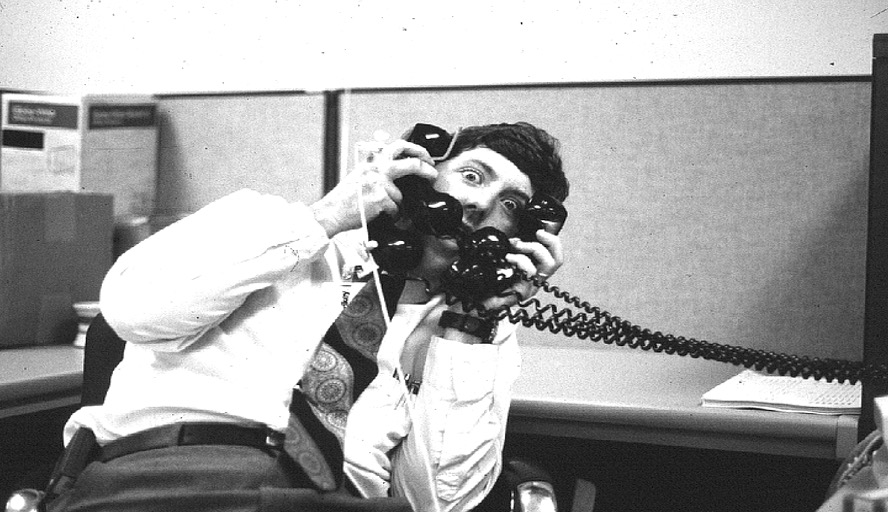

DR. KENN SATO, CHIEF OF NEUROSCIENCE AT CEDARS SINAI, stared in frustration—and no small degree of exhaustion—at the brain scan on the screen in front of him. Rubbing his eyes in the dim light of the viewing room, he muttered to no one in particular, “This just doesn’t make sense.”

Rocking back in his chair, he stared at the ceiling. The room was quiet, one of the few places in the hospital right now that was.

The frustration he deservedly felt was due to his inability to diagnose a widespread neuro-physiological malady that was rippling through societies across the globe. There was little

rhyme or reason to it; it affected young and old, healthy and infirm, men and women. The only discernible patterns were that it seemed to be focused largely, though not exclusively, on developed industrial nations; and, the symptoms were identical, regardless of age, ethnicity, gender, overall health, or race. Physicians and researchers had so far failed to identify an organic cause for what they had taken to calling Hysterical Catatonia, or ‘HysCat.’

But the name didn’t go far enough in its attempt to describe the condition. Symptoms of those suffering from HysCat ranged from extreme anxiety, to bursts of uncontrolled anger, to periods of profound, debilitating sadness, to incoherent mumbling and hand twitching, to a full-blown catatonic state in which patients stared off into space, apparently neither seeing nor hearing, their hands twitching and jerking uncontrollably. At first, they suspected something organic, like an amoebic brain infection; then, they considered Tourette’s; some thought it might be from some external inorganic cause, like ingestion of mercury (‘Mad Hatter syndrome’). But none of those panned out. Medically, it was a frustrating mystery—and it was intensifying. Whether it was organic or environmental, no one knew. But the symptoms were spreading rapidly, and nothing was slowing them down.

Sato’s reverie was broken by the buzzing of his mobile. An incoming text from his colleague, Rafael Santoro, the head of Emergency Medicine.

NEED YOU HERE STAT, UP TO MY ASS IN CASES.

Sato looked once again at the ceiling. This long day just got longer, he muttered. Pushing himself out of the chair, rolling his neck and shoulders to work out the kinks, he headed for the door and the ER.

SANTA CLARA, CALIFORNIA (AP) The world awoke this morning to an incomprehensible reality: all forms of social media had disappeared from computers, laptops, tablets, smart watches, immersive reality headsets, smart TVs, and mobile devices.

Initial speculation was that a widespread failure within the great, Byzantine machinery of the Internet had caused the applications to become temporarily unavailable, or that hackers had somehow blocked access to the vast sea of servers that housed the code that enabled the social magic.

That was not the case, however. The Internet itself was working perfectly, as were standard applications—email, search, office automation, database, storage—but the social applications were gone, disappeared without a trace. No Facebook; no Twitter; no Instagram; no Snapchat, no WhatsApp, no TikTok; no Clubhouse, no Reddit, no Signal. It was as if they had never existed. Calls to the parent companies of these services went largely unanswered; ‘We’re … working on it’ was the only response given by an ashen-faced Facebook employee who was cornered in the parking lot by a journalist and who agreed to speak off-the-record.

As a sign of the severity of the situation, reporters monitoring the various headquarters of social media companies reported that no one had left the buildings—not a single employee—in four days. The only people who had entered were food delivery drivers and a few members of the clergy. One DoorDash employee who agreed to speak on condition of anonymity said that he couldn’t wait to get out of there. “People are yelling and crying all over the place. And it smells like a high school gym in there. It’s gross.” A GrubHub employee on a Vespa nodded vigorously in agreement.

Internet security specialists dove in, attempting to find the source of the disruption. But every time they thought they had discovered the cause of the bizarre disappearance, they found themselves at a digital dead end. Nothing like this had ever happened before. Applications had certainly failed in the past; data centers had suffered power outages and gone offline; hackers had scrambled the brains of computers and made data unavailable. But never had an application with so many global users actually disappeared, much less all of them. This, if the tabloids were correct, was technological Armageddon.

One senior security professional in northern Vermont who asked not to have his name revealed, reported that he had discovered an anomaly a few hours into the initial outage, which began with Facebook.

“I can’t be sure,” he reported, “but based on what I’m seeing, there’s a pattern. Don’t quote me on this—at least not yet—but it seems as if somebody has inserted some kind of character filter, deep within the source code, that invalidates certain key text and executable strings. As near as I can tell, anything that gets transmitted—whether it’s a message between users, or a piece of parsed application code—that has certain specific words in it, is getting permanently and irretrievably deleted. If it’s a message between users, it just disappears. If it’s part of application source code, it gets deleted and the app quits working, which explains why all of these applications have gone bye-bye.”

When asked what, specifically, was being deleted, or was serving as the trigger for deletion, Joe responded that it appeared to be a fairly narrow collection of digital items.

“Here’s what I’ve found so far,” he began. “Any occurrence of the words ‘friend’ or ‘friends,’ or ‘like’ or ‘likes,’ or the word ‘following,’ triggers immediate deletion, as do certain phrases or letter combinations: LOL, BFF, BRB, BTS, BTW, DYK, IMO, IRL, LMK, AF, GOAT, LMAO, MFW, OMG, and TMI are the ones I’ve found so far that get vaporized, although my list keeps growing. Look here— FOMO and ICYMI just popped up. I’m also finding that certain images or symbols cause transmissions to disappear: the symbols—you know, emojis—for thumbs-up, waving hands, piles of dog poop, and a variety of facial expressions cause immediate and permanent deletion.”

Joe’s admiration for the elegance of the attack showed. “What’s brilliant about this hack is that the code is scattered all over the distributed servers that make up the Internet, so there’s no single place it can be fixed. We’re talking hundreds of millions of devices out there, all owned by different people. I’ve also discovered that there may be an AI element to this thing. It seems that it’s doing video analysis, and going after specific video sequences. If the AI algorithm sees a character in a video that stares at the camera and pulls on their clothing three or more times, or if the star of the video has lips that look like they were stolen from a carp, or if the person in the video’s face is less than two inches from the camera when the video starts, the video is trashed. Also, anything that involves cats or politicians seems to be targeted, although for some weird reason, videos with Bernie Sanders are left alone as long as he’s wearing those mittens.”

Within hours, emergency rooms began to fill with frantic patients suffering from symptoms of dopamine withdrawal caused by the sudden disappearance of likes in their lives. Medical personnel were forced to tell each patient how great they were, how valuable they were to society, and were strongly encouraged by psychiatric staff to give every patient two thumbs-up every time they walked past a treatment room or gurney-bound patient in the hallway. It was exhausting.

“It takes a lot of extra time, but it’s what they need. Otherwise, they quickly descend into a dark depression that we can’t pull them out of,” said Dr. Kenn Sato, department head of Neuroscience at Cedars Sinai Hospital. “It’s just a panacea, but it’s the only thing we have at the moment that seems to have any effect at all. But it has to be done consistently. And I mis-spoke there. Let me be clear: we haven’t pulled anybody out of this yet, whatever ‘this’ is.”

THE BOARDROOM TABLE IN FRONT OF WALT HARRINGTON was a work of art, inlaid with precious stone and wood inlay. On it were plates of fruit and cookies, pitchers of water, and carafes of coffee, all laid out for the 16 people who sat around the table. Seated in their expensive Recaro chairs, they looked at him silently. They all looked as if they had eaten bad shrimp.

“I’m sorry about that,” Walt told them in a quiet voice, trying unsuccessfully to look contrite, his palms raised toward them in contrition. He had spent the last five minutes pounding the table with his fists, Khrushchev-like, as if abusing the table would give his words more impact.

“I’m not directing my anger at you” (he was), and I’m not being overly dramatic (he was), but I need to drive home just how bad this is (they already knew). We’ve lost access to our most accurate indicator of market performance.”

He turned to face the windows behind him and ran his hands through his thinning hair. His jacket spread out like butterfly wings. He turned to face the people in the room. His mouth opened, closed, opened again. He looked like a trout in a stream. He was at a loss for words. He dropped his arms to his sides, which apparently dislodged something, once again giving him the ability to speak.

“Our entire market strategy—shit, our entire customer engagement strategy—is based on

Measured Return on Likes. You all know that. We’ve spent years perfecting it. And now the likes that feed it have fucking disappeared! We’ve got nothing. I feel like we’re sailing in the fog. Unicorns and rainbows don’t cut it, people—come on, you’re the senior leadership team! How do we get around this? How do we get insights on customers without social media feeds?”

The people gathered around the table looked at each other uncomfortably, but no one spoke. Most just stared at their uncontrollably twitching hands. Then, a single arm went up. It was attached to Ed Adams, the firm’s Chief Counsel. His suit was expensive; his tan was perfect; his silver hair perfectly complemented his leonine face.

“Ed?” Walt Harrington gestured, yielding the floor to his colleague.

Adams drank from his coffee cup before responding. He smiled, his hands folded across his stomach. “Why don’t we call them?” he asked.

Harrington looked at him, his face puzzled.

“Who? Call who? What the hell for?” His frustration was beginning to well up again.

“Why, customers, of course,” Ed responded, “Why don’t we just call them, and ask them how happy they are with the product?”

Titters around the room. Harrington stared at the inlaid tabletop and sighed deeply.

Looking up, fixing the attorney with a steely gaze, he asked the room, “Does anyone have any realistic ways to get us out of this mess, or are we just pulling suggestions out of our collective asses?”

A SECONDARY IMPACT OF THE DISAPPEARANCE OF SOCIAL MEDIA was that the global supply chain was reeling. One economist, who couldn’t stop giggling during the interview, said, “Well, of course it’s in trouble! Don’t you see? Without social media, people have no way of knowing what their ‘friends’ are wearing, thinking, eating, drinking, playing, or doing, and since social media makes it impossible for people to make their own decisions about what they want to wear, think, eat, drink, play, or do, they’ve stopped spending money, because they’re not seeing hyper-targeted ads that tell them how and where to spend it. Large pieces of the global economy have just come to a halt. It’s the end of everything! Without the influence of—you know, social media influencers—the world has no compass to drive it forward!”

Sociologists were quick to point out that this could mean the end of civilization as we know it. One authority, who agreed to speak on condition of anonymity, observed that the disappearance of social media could lead to societal breakdown for two main reasons. First, he said, a significant number of multinational corporations base their growth strategies and revenue projections on MROL—Measured Return on Likes. Without powerful performance indicators like Yelp, he told the reporter, there are no likes, which means that there is no success indicator available against which to benchmark—well, anything. Some organizations have already gone so far as to indicate that they may have to fall back on outdated legacy measures, like delivering on the promise of customer experience and baseline profitability. Some have intimated that they may have to start hiring people on a full-time basis, paying them well and giving them legitimate benefits as a way to create employee loyalty, which some studies from the 90s indicate leads to employee loyalty and therefore higher levels of customer engagement and stickiness, although all queries regarding such intentions were quickly dismissed as groundless rumor. ‘We’re a long way from something that extreme,’ most company representatives were quick to say.

The second reason cited was far more sinister. For years, people have forged what they believe to be strong, heartfelt friendships on social media platforms. “Those were my people!” one teen cried as she collapsed to the ground, her phone clutched tightly in her hand, its screen displaying a quaint address book application that said, ‘NO ENTRIES.’ “They were my everything! What am I supposed to do now?!?!?” Aid workers helped the girl to her feet before hustling her off to a crisis center. As she was loaded into a waiting ambulance, she could be seen mindlessly swiping the screen of her phone, but she wasn’t looking at it. As the ambulance attendant closed the rear doors of the vehicle and gave the driver a thumbs-up, the girl smiled broadly.

ROGER BOUGHTON EMERGED FROM THE BASEMENT carrying a dusty, dented cardboard box, on which someone, probably him, had written with a black marker, ‘OFFICE.’ He placed it on the kitchen table in front of his son who sat there, glassy-eyed. He could hear his 16-year-old daughter upstairs, crying, his wife trying to console her.

This is a serious Hail Mary, he thought. It’s crazy, but I can’t think of anything else.

He pulled a steak knife from the knife block on the island and proceeded to cut open the now-brittle tape that barely held the box closed. He set the knife aside and folded back the flaps.

Reaching into the box, he began to remove the annals of a former life: a black, two-tray plastic inbox; a pile of long out-of-date technical papers, now faded to pale yellow; his Franklin Planner, the leather cover cracked and stiff; a handful of number two pencils from the Blackfeet Indian Writing Company; a stack of business cards, the rubber band holding them together long since gone brittle and broken; a sheet of 17-cent First Class stamps; his desk dictionary; the coffee cup given to him by his team years ago, during a difficult time, with the legend, ‘NON ILLEGITIMI CARBORUNDUM’ (DON’T LET THE BASTARDS GRIND YOU DOWN) printed on it, in fake Latin; a paper-clipped pile of Xeroxed office humor, pulled from his cubicle walls, the paper clip creating a rusty palimpsest of itself on the top page; his HP 12c calculator; a VHS tape with who-knows-what recorded on it; his college slide rule; a stack of plastic stenciling templates; a sheet of camera-ready clip art; and finally, at the bottom of the box, his 2500 set, still connected to its long, gray, RJ-11 tether.

“What the hell is that?” his 13-year-old son asked.

Roger ignored the question from his son as he undid the twist-tie that kept the coiled gray cable from expanding, then bent over and plugged the clear plastic clip into the long-ignored outlet on the kitchen wall with a satisfying click. He picked up the handset, held it to his ear, and smiled. “Oh yeah…” he said.

Pulling the ancient desk phone over to the kitchen table, he placed it in front of his son. “There you go—call Devin,” he said, referring to his son’s best friend.

“How?” his son asked.

“Just punch in his number.”

“What number?”

WITHIN A FEW DAYS OF THE ONSET OF THE CRISIS, first responders began to intervene sporadically but effectively with tools and techniques to help the most afflicted deal with the trauma of anonymity. Fire stations across North America marshaled resources to gently teach people how to use the telephone function on their mobile devices, and in one extraordinary case, taught them how to use sheets of paper and pens or pencils to draft and mail letters through the U.S. post office. Most such efforts were illegible, but the act of licking the stamp and envelope seemed to calm many of the afflicted.

Some scientists have taken to calling the behavior that has resulted from the disappearance of social media ‘the Ptolemy Rebound,’ referring to the fact that when under the thrall of social media, individuals rapidly begin to believe that they are at the center of the universe, in the same way that Ptolemy’s followers, including the Catholic Church, believed that the Earth was at the center, until Copernicus, Galileo, and Newton proved otherwise. Clinicians have begun to refer to the ‘deprogramming protocol’ they have developed as the ‘’Defamation Process,’ referring to the slow but gradual process of weaning people off the fantasized sense of individual fame and galactic importance that social media use creates.

I’ve seen ERs in Beirut that looked better than this, he thought.

RAFAEL SANTORO LOOKED OUT ACROSS THE HOSPITAL GEOGRAPHY that was his responsibility—the Cedars-Sinai Emergency Department. At the best of times, he had 51 beds available for walk-ins, but these weren’t the best of times. This was somewhere on the other side of Code Black. Gurneys, cots, and makeshift litters covered every square foot of space, and every one of them was occupied.

Demographically, the patients were all over the map, although the population of the afflicted leaned more toward a younger audience. Some lay on gurneys, staring glassy eyed into the distance. Some sat upright, rocking back and forth as if they were praying at the Wailing Wall, their fingers twitching in their laps. All of them randomly slapped their hips with hands every couple of minutes, responding to phantom vibrations caused by imaginary incoming social media notifications. It was as if a body part had been amputated—phantom limb pain.

Santoro walked out into the hallway, which had been converted into a triage area. He watched as a nurse took a patient’s clunky shoes from their bag of personal belongings under the gurney and wedged them under the patient’s pillow. What the hell?

Walking over, he accosted the nurse, asking what she was doing.

“We don’t have a choice,” she replied. “We’ve run out of extra pillows, so we’re using whatever we can find to prop their heads up.”

“But she has a pillow,” Santoro replied.

“It’s not enough. All these people need at least two pillows, because they can’t put their heads down that far when they’re lying on their backs.”

He was mystified, but just for an instant felt a ray of hope that quickly vanished. “Why? Are they showing signs of meningitis?”

“No, no, nothing like that. They’ve spent so much time with their heads tipped forward looking at their phones that their necks don’t tip back anymore without severe pain. We figure they must all sleep on their bellies or sides. So, we have to prop ‘em up any way we can, or they’re in pain and want meds.”

“Rafa!”

He turned at the sound of his name and saw Kenn Sato walking toward him. Sato passed a young woman lying on a gurney in the hallway and gave her an exaggerated smile and two thumbs-up, before looking at Rafael and rolling his eyes.

“How’s it going?” Sato asked.

“Shitty, thanks,” he replied. They walked over to the staff lounge to help themselves to steaming cups of hot coffee, the one amenity in the hospital that was never in short supply.

“This is the shit show of shit shows,” Santoro groused. “All these parents are bringing their kids in for help. Problem is, they’ve all gone online and looked up symptoms in the online PRG, and

half of ‘em are convinced their kids are jonesing for coke.”

Sato shook his head. “Nope. It’s withdrawal, alright, but not cocaine. It’s Dopamine Agonist withdrawal. Same symptoms. “I’m pretty sure—”

They both went quiet as the ER intercom clicked to life with a scratch of static.

”Dr. Sato, Psych consult, exam 4. Dr. Sato, Psych consult, Exam 4.”

“To be continued,” Sato said, slugging down the coffee. Turning, his hands in the pockets of his lab coat, he walked back onto the floor and headed across to the treatment room area, where a bevy of nurses in Exam 4 surrounded a young girl and her anxious parents. Even from the other side of the ER, he picked up on the stress in the room. Walking over, he stood at the door, took a deep breath, mentally calmed his voice, and called to the Charge Nurse who was standing at the head of the bed, speaking quietly to the girl in the bed as she gently rubbed her forehead. He could hear some of what she was saying: “…of course they remember you … you’re not going to miss out on anything … of course they still like you …”

The girl whimpered and mewled at her touch.

At the sound of her name being called, Deb Long looked up at him and smiled, her face wan and drawn from exhaustion. “This is Dr. Sato,” she said, turning to the girl’s parents. He’s one of our … specialists.”

They turned to him as all parents did in times of crisis, glomming onto him like a drowning swimmer trying to climb to safety atop an approaching lifeguard. He picked up the chart from the slot at the foot of the bed, perused it, put it back. He sat down on the foot of the bed, smiled at the young girl, and asked, “How are you feeling, Amber?”

CAROL BORGHESI, CRISIS RESPONSE LEADER FOR WESTERN CANADA, was quick to point to another phenomenon that she was watching with great interest.

“People are crawling the walls over activities they think they’re missing out on because of the disappearance of social media,” she observed. “It seems to be an irrational Fear of Missing Out that has people reacting this way—they call it FOMO. Apparently, when they’re chatting with their friends online, they think they’ve been transported to some alternate universe where stuff they talk about actually happened. One group of teenagers couldn’t shut up about the day they all saw a whale jump out of the water and land on a fishing boat, when I know for a fact that they’ve never—not a one of them—ever been more than five miles from Kelowna. You know about the madness of crowds? I’ve been putting out fires like this for a very long time, but for the life of me I can’t figure out what activities it is that they’re apparently missing out on. Their minds are just making shit up and convincing them they were there the day they found a real mummy in a Wal-Mart in Seattle. It’s mystifying to me.”

“IT’S NOT ‘DEFAMATION’ AS IN, CONDEMNATION,” said Doctor Kenn Sato, head of clinical neuroscience at Cedars Sinai, one of the hospitals that had had early success in at least treating the symptoms of HysCat. “It’s ‘de-famation,’ meaning to de-fame—weaning people off the false sense of fame that they all seem to have, this Messianic behavior that makes people believe they’re more famous, have more friends, are better known, and are more influential than they actually are. One of the techniques we’re using—and let me go on record here to say that we’re doing this with extreme caution, under very carefully controlled clinical conditions—is to slowly—let me repeat that, very, very slowly—show them an occasional downward-pointing thumb. It’s a radical step, and it’s potentially dangerous, but extreme situations call for extreme measures.”

“HELP ME UNDERSTAND THIS, BOB. One minute we’re up to our assholes in loudmouth, extremist dipshits, yammering that the planet is circling the drain, and then it’s all sweetness and light and unicorns farting rainbows and glitter. What gives?”

The question came from Carl Potter, a high-ranking presidential advisor who prided himself on his deep understanding of both domestic politics and foreign affairs, and the places where the two touched. The fact that he was asking the question spoke volumes about the magnitude of the current situation. Carl was one of those guys who always had all the answers—and if he didn’t, he made some shit up with such flair and certitude that no one ever questioned him. And, even when he was pulling answers out of his ass, he was usually right. And, even when he was wrong, he was so confidently wrong that he sounded right. He was an extraordinarily gifted politician.

“Yes, it is weird, isn’t it?” Bob replied. Bob Catella was a White House consultant on societal affairs, with a background in sociology and industrial psychology. “I’ll be the first to admit it, but things are weirdly calm, politically. Ever since 2016, we’ve watched the extreme ends of the sociological and political bell curves in countries with access to social media become the tail wagging the dog,” he explained. “There was a time not all that long ago when the extreme thinkers—what we professionally call the whackadoodles—had voices that, from a loudness point-of-view, were in keeping with their percentage of the overall population. Then social media arrived, and suddenly those tiny factions had megaphones, which gave them outsized voices, far bigger and louder and, let’s face it, scarier than their owners actually were. They became the 21st century equivalent of The Mouse That Roared” —referring to Leonard Wibberley’s 1955 satirical novel in which the tiny Duchy of Grand Fenwick defeats the world’s superpowers. “I call it the Wizard of Oz effect,” he continued. “Now, with social media gone, those groups out there at the edge still have a voice, but it’s gone back to being an inconsequential whisper in keeping with the size and actual relevance of the groups supporting their fringe messages. They’ve gone back to being the ‘Who’ in ‘Horton Hears a Who.’”

PEOPLE ACROSS THE SPECTRUM have slowly, gradually, haltingly begun to engage in bizarre rituals, heralds of a bygone age. Thanks to support programs that were quickly thrown together at the community level by legacy, face-to-face organizations like Rotary, Kiwanis, and Lions Club, they’ve met their neighbors and, in some cases, have actually gotten to know the names of their neighbors’ children. People have been spotted going for walks with people to whom they are not related, and in an inexplicable turn of events, few wear noise-cancelling ear buds or headphones—they’re actually engaged in conversation with other people. And while it took some time, people have learned how to carry on a conversation over dinner without inviting their mobile devices to join them.

Another odd thing that has surfaced—or, re-surfaced, as one older wag was quick to point out—is the Welcome Wagon. “We’ve started to see them in neighborhoods again,” one woman told a reporter from her front porch. “It was the strangest thing—we just moved into the neighborhood, and the day after the movers left a car pulled into the driveway and a woman got out with a big basket of flowers and kitchen stuff. It was pretty wonderful. And get this—as she was leaving, one of our neighbors from across the street came over and handed me a casserole. A casserole! I love casseroles! I haven’t had a casserole in years!”

TIM COOK SAT AT THE HEAD OF THE TABLE inside the cramped Secure Compartmentalized Information Facility, or SCIF, on the top floor of the great Apple doughnut in Cupertino. The room was basically a room within a room, acoustically and electronically isolated from the world to ensure that eavesdropping on conversations carried on within the space was not possible. It floated above the floor on vibration-dampening isolators and was wrapped in a copper mesh skin to prevent signals from entering or leaving the SCIF. As an extra precaution, mobile devices were not allowed inside. Only a few people at the company were aware of its existence—including those who were there today.

“This is an all-hands-on-deck moment, people,” he told them. Nine faces looked at him expectantly, the nine most senior and creative people in all of Apple. “We have an opportunity here to capitalize on a once-in-a-lifetime event that might change the face of this company in profound ways and uncover opportunities for us that no one else is looking at, if our market analysis is correct—and I have every reason to believe it is. The disappearance of social media has been painful for much of the world’s population, but there are some things we can do to reduce the pain, things that will have our logo all over them. We’re going to have to do some acquisitions—I know, that hasn’t traditionally been a big part of our history—but thinking different certainly has.”

He paused to look up at the framed photo of Steve Jobs on the wall. “I’m going to walk you through my thinking, and I want solid pushback wherever you think I’m off base. This is not a time for humility, shyness, or fear—if I’m wrong, tell me, because I’m not going to bet the ranch on a half-baked idea. So: here goes. The first thing I want to do is …”

IN A SERIES OF DEFT MANEUVERS THAT MANY WOULD LATER CALL STEALTHY, and in some cases reckless, Apple engaged in a series of bold acquisitions that no one saw coming, because no one else saw the genius in what they were building. It went far beyond a newly introduced product or product line; it was almost a philosophy.

iAm

Over a period of 48 hours, Apple closed in on and acquired, in Blitzkrieg fashion, eight organizations: Faber-Castell; Ticonderoga; Paper Mate; Visconti; Mohawk Paper; Strathmore; the pen division of Mont Blanc GmbH; and in what many suspected was driven by hallucinogenic mushrooms, the U. S. Postal Service. After negotiating an agreement to use the name with a national pet food company, they called the organization that resulted from the merging of the newly acquired companies, iAm.

At Cook’s urging, and in concert with the Vermont-based Emily Post Foundation, Apple also commissioned the creation of an app designed to provide on-demand social skills that would help people through the awkward moments associated with carrying on a person-to-person conversation, in real-time.

“QUIET DOWN, PEOPLE, QUIET DOWN, PLEASE.” Dr. Kyle Mayer exhorted his classroom to settle down. His was a medium-size lecture hall that sat about 250 students, but right now, it was packed, standing room only. Insane.

This had happened ever since he announced his new course in the Communication Arts Department, “Applications of Non-Electronic Communications Media.” At first it had been a joke, but he’d said something about it to another professor in the cafeteria one day a bit too loudly, and one of his students overheard.

“I think that would be a great course, Professor M.,” he effused. “That’s like lost art stuff—ink-stained fingers, leather elbows, linen paper, and licking stamps. I am so in.”

They spoke about it for some time, and a few other students joined the conversation. Kyle came away with the idea that there just might be something to this. He floated the concept at the next department meeting, and the response was cautiously positive. So, he put together a course description and syllabus.

Media Studies MS117 Course Syllabus:

Applications of Non-Electronic Communications Media

Professor Kyle Mayer

Barrows 221

The purpose of this course is to introduce students to a variety of non-electronic interpersonal communications modalities that were popular in the late 20th and early 21stcenturies, and that continue to offer potential in both personal and business settings. Participants will learn about the origins of these techniques, how they evolved to electronic alternatives, why some of these media failed, and how to use these legacy solutions effectively. Topics covered include:

- Loss of social media and its Sociological, Cultural, and Economic Impact

- Electronic Communication Tools that Remain Relevant

- Computer-based voice applications

- Legacy Tools—Applications and Insights

- Telephone (i.e., voice calls)

- Telephone Protocols

- Effective Voicemail Techniques

- Proper Telephony Etiquette

- How to have a conversation: the fine and deliberate art of listening

- Letter-Writing Protocols

- Envelope Addressing Techniques and Options

- Stamp Selection and Application

- Lessons in Patience and Altered Immediacy

- Rewards of delayed gratification

- Fact Verification Techniques and Effective Research Skills

- Developing Healthy Skepticism

- Recognizing Truth and Falsehoods

- Social Engagement and Healthy Disagreement

- The inalienably important role of reverence

- Dealing with Confirmation Bias

- Active Listening vs. Passive Hearing

RICHARD DREYFUSS WASN’T SURE WHY HE HAD BEEN SUMMONED, but he had an idea. In the early 2000s, he had spent time at Oxford University as a research fellow to study Civics, which he defined as ‘an individual’s involvement as a citizen in the political activity of their nation and maintaining civility and civic discourse.’ He had gone on to teach classes and workshops on the subject, because of his strong conviction that the subject matter, which had begun to disappear from school curricula in the 1970s, was critical to a healthy society.

He was pulled from his musings by a voice calling his name.

“Mr. Dreyfuss? The President will see you now.” He rose and accompanied her through the thick door into the Oval Office.

“Richard—may I call you Richard?” the President asked.

He nodded, assenting to be called by—well, his name. The President nodded back.

“We’re at a watershed moment, Richard,” the President said, earnestly. “Whatever it is that killed social media has done us a huge favor. People are running around like a pen of Thanksgiving butterballs without any life guidance. They have no idea what to do right now, so I want to strike while the iron is hot, as they say, and I need your help to do it.”

Dreyfuss swallowed. “What is it, exactly, that you want me to do?” He asked.

“I need a chief protocol officer,” the President replied, “Someone who can help me restore some degree of decorum to society. We need to get a few things back into the classroom and get them rooted in peoples’ heads, like civics, debate, geography, and history, and we need to start a national conversation about why they matter. Hell, I’m thinking about starting National Term Paper Day and National Debate Day. Social media started this belief that if somebody thinks differently than I do, then they’re wrong, they’re an idiot, and they’re my enemy. What a crock. I need to get people thinking again about the power and richness of diverse ideas. Can you help? Are you my guy?”

THE ENVELOPE THAT SHE PULLED EXCITEDLY FROM THE MAILBOX was hefty. Walking back up the driveway, Anna MacTavish tore at the hand-addressed envelope from her daughter, Ella. She knew what was inside, and she knew it was coming. And now, finally, it had arrived. The wait had been deliciously infuriating.

Pulling the bundle from the envelope, along with the accompanying letter, she made it as far as the porch before she succumbed to curiosity and sat down. The stack of photos, a quarter-inch thick, was of her new granddaughter, Jonnie-Laura. She was every bit as precious as her own daughter had said she was, a smiling, round little baby, with perfect fingers and toes. They’d spoken on the phone, and they’d had a couple of unsatisfying Zoom calls, but Jonnie-Laura was either asleep or unwilling to cooperate with the camera.

Dear Mom,

Sorry this took so long to get to you, but as you can imagine, things have been a little crazy around here. Tom and I are still not getting much sleep, but hey—that’s what we signed up for, right? We’ve only had this little girl for a week, but I already understand everything you’ve always said about how having a child changes you forever. I was on the phone this morning with my friend Rae—you remember her, she lives in Oklahoma City…

ST. AUGUSTINE IS REPORTED TO HAVE OBSERVED THAT “The reward of patience is patience.” John Comiskey thought about the quote, which his girlfriend had shared with him, as he waited for the bus that would take him to campus. He knew that it would be along in about a half-hour, so he had time to get a little reading in. There was no hurry; if he got bored, he’d do a little journal writing on his ReMarkable tablet.

“I DON’T CARE—GO OUTSIDE AND PLAY!”

Andrea Mills had had it up to here with her two boys. As her husband liked to say, she had one nerve left, and they were getting on it with their incessant fighting, arguing, and whining. After a long day at work, all she wanted was to fix dinner (which she enjoyed if she was uninterrupted) and nurse a Bees Knees while she did so, the gin and honey leaving her mellow and relaxed.

Looking up from the cookbook on her iPad, she saw that the boys were pulling on their shoes. 11-year-old twins, they did everything together, including squabbling. But it would be a couple of hours before dinner was ready, so they had time to go outside for a while. She knew that most of the kids in the neighborhood would be out playing while their own parents fixed dinner and relaxed.

Rushing the door, they called out, “See you later, Mom!”

“Be back by 6:30!” she yelled back. The door slammed; she knew they had heard her, which meant that she would have to holler at least three times to get them to come back inside to eat. It’s pretty wild, she thought. Ever since social media shit the bed, it’s like some kind of imagination gene has kicked in. The electricity-free wasteland outside the front door actually offered some interesting things to do that didn’t require gadgets, and the kids had discovered them. Miraculous. She knew they wouldn’t wander off; lately, they hadn’t gone any farther than the dirt under the shrubs in the front yard, where they had constructed a metropolis of roads using popsicle sticks as graders and stockades made of twigs cut with their pocketknives.

“JOHN!”

John Comiskey looked up from the book he was reading to see his girlfriend standing in front of him, staring down with a half-smile on her face, her arms crossed over her chest.

“Oh—hi. Sorry, I was reading.”

She smirked. Yeah, I can see that,” pointing at the book in his lap. Listening to the Continent Sing, she saw. “I only called your name three times. And you just missed your bus.”

His mouth opened, then closed. “Sorry—this is really good,” he said, holding up the book. “It really sucked me in. I can’t believe how much time I read now. Speaking of that, are we still going to the bookstore tonight after class? It’s apple pie day in the café, and I’m planning to get there early to stake out our favorite table…”

TIM COOK STARED OUT THE WINDOW OF HIS OFFICE at Apple Headquarters in Cupertino. His gamble, risky though it might have been, had paid off. Even though email and texting were still active and working around the world, the loss of social media had left a void that Apple had filled with iAm. Yes, people still lusted after the latest mobile device, but it was mainly for calling each other and taking pictures and videos. But they had become equally lustful for the latest retro Apple mechanical pencil, or for those with money, the first to own a beautiful fountain pen from any of Apple’s newly acquired subsidiaries. In fact, ‘cool’ was now defined by a pad of paper (jokingly referred to as the new iPad) and a couple of yellow number two pencils sticking jauntily out of a shirt pocket. And thanks to their relationship with the U.S. Post Office, which they were now in the process of privatizing, one of Apple’s most popular apps was ‘iStamp,’ with which users could create custom postage stamps and mailing labels that matched their personalities and interests.

So strange, he mused. Email and text were still in widespread use for businesses, and while they still had their place for interpersonal communications, their use was way, way down in favor of analog communications—phone calls, notes, letters. He smiled as he thought about 3M’s recent announcement of a 600 percent increase in demand for post-It notes, driven largely by kids wanting to leave surreptitious messages for each other in secret places. There had also been an uptick in demand for the geocaching apps on the Apple App Store, as kids looked for things to do outside.

SAN RAMON, CALIFORNIA WAS A BEDROOM COMMUNITY, an East Bay outgrowth of the greater San Francisco metroplex. Originally the site of endless walnut orchards, in the late 1970s developers began to acquire the land to turn it into relatively low impact business parks. What they didn’t count on (but were quite happy about) was the mass exodus of large-scale businesses that fled San Francisco during the 1980s because of a lack of adequate public transportation, clogged freeways, a dire lack of affordable parking, and out-of-control taxes. Most of them reestablished themselves in San Ramon and Dublin, the town just to the south of San Ramon—or SRV, as its residents and workers soon began to call it.

But San Ramon was now known for something else: its public library. At 50,000 square feet, it was one of the largest municipal public libraries in the state, perhaps in the country, and its community programs were renowned. The library had become the gathering place for children and adults alike, and while they offered what all libraries offered—books, audio books, and music to check out, computing and computer application classes, as well as robotics kits and theater paraphernalia, they also ran workshops on public speaking, storytelling, writing, reading, Podcasting, geography, history, and travel, and they were giddy to announce that there were waiting lists for almost all of them. The San Ramon Community Library had, in many ways, reconstituted itself as the town’s Community Center, in the truest sense of the phrase.

“IS ANYBODY ELSE SEEING WHAT WE’RE SEEING?” the head of the Chamber of Commerce of Weirton, West Virginia asked of the assembled group. The meeting was a gathering of eastern state Chamber of Commerce leaders, all intent on improving the lot of their communities. “Are we alone in this?”

A buzz went around the room before a hand went up, this time, the head of the Chamber in Plattsburgh, New York.

“Nope, we’re seeing it, too,” she told the group. “At first, we didn’t track it, but then, because it got so weird, we just had to. Want to compare notes?”

They did—all of them. At ten-person round tables, they discussed what they were collectively seeing in their towns, and while it was all over the map, it wasn’t. Downtowns, which in many cases were suffering from post-COVID morbidity, were suddenly lighting up as demands for retail space following the disappearance of social media went through the roof. “They want to open an ice cream parlor!” said one delegate. “Bowling alley!” said another. “I’ve got three investors who want to turn the old mall into a roller-skating rink!” said a third. The news bits got tossed about the room like shrapnel.

“What about the bookstore thing?” yelled the person from Staunton, Pennsylvania. “We went from nothing to three bookstores in a year, and they’re busy. They all have coffee shops that just serve coffee and espresso and iced tea and cookies, and the lines are out the door.”

“And did you hear about the kinds of books they’re selling?” asked another delegate. There’s a scramble on to update and revive the old series books. I just read in Publishers Weekly that Random House is scrambling to round up a stable of writers who can crank out words, because suddenly there’s demand for Cherry Ames, and the Hardy Boys, and Tom Swift, and Doc Savage. Kids are asking for the Happy Hollisters, for Christ’s sake!”

In the back of the room, an attendee sat quietly and patiently, his hand in the air. When a lull in the conversation finally happened, the chair of the meeting acknowledged him.

“I’m not from a Chamber of Commerce,” he said, “but I’m a manufacturer’s representative for a lot of the companies that supply your retailers. What I’d like to know is what you’re seeing in the way of purchasing trends. What are people buying, and what are they asking for that you don’t have? What message can I take back to the companies I represent that will help them be ready for coming demand? Is that something you can tell me?”

The group agreed to work at their tables to come up with lists of the things that they were suddenly and unexpectedly seeing demand for. The list was—weird.

Roller skates

Pocket knives

Yo-Yos

Office supplies

Silly Putty

Matchbox Cars

Walkie-Talkies

Slinkies

Tetherballs

Model airplanes

Balsa Wood

WASHINGTON’S BRAHMINS HAD NO PLACE TO GO. With the disappearance of social media, their ability to control the messages they wanted delivered to their constituencies had no outlet—the conduit of control was gone. Social media had made it possible for them to deliver exquisitely targeted messaging that would instill just the right amount of fear and discontent, and to receive, in near real time, feedback telling them how well their micro-campaigns were doing their jobs so that their people could engage in the endless bit-twiddling that needed to be done to keep messaging on-track. And, social media gave them access to the tool that shall not be named: the careful spread of just the right amount of carefully crafted misinformation to create anger, frustration and fear. But now, that mechanism was defunct. Their world has gone dark; they were whistling in the political graveyard.

But then, strange things began to happen in Washington. An invitation to attend a barbecue in the back yard of a Republican staffer went out to the entire Senate—Senators and staff alike. Only about 40 of 100 elected officials showed up, but they were pretty much evenly matched in terms of their political leanings.

“Welcome everybody!” said the host to the collected but awkward group, raising a can of beer and gesturing toward the green expanse of the back yard. “Anybody want to play cornhole?”

Other invitations followed; soon, whichever Senate members stayed in Washington over any given weekend began to attend the gatherings as a matter of course. During one particularly vexing game of Twister, during which Lindsay Graham memorably tore his gluteus maximus, a staffer from Kentucky made a rather insightful observation. “Other than the unfortunate lawn dart incident which had happened early on (and which everyone now claimed to have been an accident), attendees from opposite sides of the aisle hadn’t even raised their voices at each other. Sure, there was the standard ribbing and gamesmanship that came with the job, and that one politically awkward evening of pin the tail on the donkey and the elephant-shaped piñata that someone anonymously brought to a gathering, but, she noted, “Everybody gets along pretty well—and I don’t know about the rest of you, but I’ve learned a lot coming to these things.” At that, she smacked Jon Ossoff on the ass and took off across the yard, yelling, “Tag—you’re it, Jon-Boy!”

Without hesitating, Jon-boy took off after her.

“WELCOME TO CIVICS 101,” KYLE MAYER SAID, as he greeted his other class (he had already taught the non-electronic media class that morning and was surprised to see many of the same faces in this one) on the first day of school. Another room full of the great unwashed masses, he thought, eager to learn. Wait a minute: was that a Big Chief Tablet on that kid’s lap?

“This course is about the craft of civic engagement,” he began. “It’s about the peaceful coexistence of disagreement and understanding. A famous person once observed that one of the most difficult things for humans to do is to hold two conflicting ideas in their minds at the same time—like disagreement and understanding. For example, we’re going to learn that it’s possible for two people to fundamentally disagree on an important issue, an issue that might be national or even international in its scope, and still like each other—still want to go out for coffee after disagreeing. We’re going to learn that it’s possible to listen to an idea that contradicts what you fundamentally believe, but after listening to the other person explain their idea—the one that you thought was so terribly wrong—perhaps you change your mind about the ‘rightness’ of your own idea.

“We’re going to explore the idea that it’s possible to use conflicting concepts to catalyze change that in the end, both disagreeing parties can support. We’re going to spend time with the idea that it’s possible to understand that a belief proposed by someone else, a belief you completely disagree with, isn’t necessarily wrong. And we’re going to learn that being wrong is not a sign of weakness—to be wrong is to be strong. And finally, we’re going to learn about inoculation.”

Hands went up all over the lecture hall. He pointed to a student in the second row.

“Isn’t that biology?” the student asked.

“Maybe,” he replied. “But it also applies here. Let me be very clear about something, and I want you to listen very carefully to what I’m about to say. In this class, and in college, and throughout your lives, you’re going to hear things—sometimes shocking things—that you don’t agree with. When that happens, and it will, and frankly, it should, the experience shouldn’t send you screaming from the room, triggered to go blubber in a corner somewhere, looking for somebody to blame for the fact that you don’t feel comfortable because somebody floated an idea in your direction that contradicts what you believe to be true. This is how the world works. Over the course of the next nine weeks, I hope to get you all to a point where, when you hear something that you don’t agree with, something that rocks your world and disrupts your thinking, you’ll sit back and say, hey, that’s an interesting idea! I don’t happen to agree with it, but it’s an interesting position. Now, what can I learn from it?”

A wave of murmur washed over the room like a spring tide. “How is that a good thing?” the same student asked, bewildered.

“It’s a good thing for two reasons,” he explained. Careful, here…don’t want them to run screaming to the Dean on the first day of class. “First, if you disagree with what you hear, that’s great. In fact, it’s your right, and in many ways, as a responsible citizen and certainly as a responsible thinker, it’s an obligation. But the best way to think of it is as an opportunity to test what you do believe. If your idea can stand up to a challenge from a conflicting idea, then after careful analytical analysis, what we call ‘critical thinking’ in this class, then your idea not only survives, but it’s stronger.”

“And the second reason?” the student asked, furiously writing in her tablet.

“What if you’re wrong?” he proposed.

The room fell silent. All writing stopped—the scratching of pens and pencils, the turning of pages. The same student looked up, opened her mouth. Nothing came out.

“Look, your thinking isn’t always going to be right,” he gently explained.

Careful, here…don’t push it…

“Sometimes you’re going to discover that what you think you know, what you believe, is just—wrong. It happens to me all the time. And while that may make you uncomfortable, or embarrass you, wouldn’t you rather endure a bit of discomfort than go through life being wrong? An encounter with different thinking is an opportunity to test the validity of your ideas. It isn’t a threat to them. And it certainly isn’t a threat to you personally.”

More hands went up. He pointed to the girl with the Big Chief tablet in her lap, now filled with scrawlings.

“I’m still confused about you mention of inoculations.”

Mayer smiled. “When we get vaccinated for something, whether it’s COVID, the measles, polio, smallpox, flu, chickenpox, or whatever, what’s actually happening there?”

Nobody spoke.

“Well, what’s happening is that your body is being introduced to something it doesn’t agree with—in this case some kind of a biological agent that, if ignored, will make us sick. What the vaccines do is try to understand the disease agent, whether it’s a bacterium or a virus, and create an effective response to the threat.

“So, if you think about it, isn’t that what we’re doing here? The only way to be able to respond to an idea that we disagree with is to understand where the person tossing out the idea is coming from, so that we can craft an effective response. That’s why I use the analogy of inoculations: I’m going to teach you how to inoculate yourselves with curiosity and knowledge, which are two of the most powerful disease agents ever created.”

He could hear the silence in the lecture hall fade as pens and pencils once again scraped across paper, as the students sucked up what he was saying. Dodged a bullet.

A hand went up.

“Question?”

The hand went down. “Professor, will we get into debate techniques in this class?” The student asked.

Mayer smiled. “Oh yeah—debate lies at the heart of civic engagement. Debate is where we’re going to show you how two conflicting ideas can be worked through so that everybody wins. In fact, we’re going to take a field trip in March to observe Town Meeting in Vermont, where they still gather in the school auditorium to decide important issues…”

“MOM, WHERE’S—” Jordan looked down at the red and blue air mail envelope in his hand— “Bratislava?”

Kathy looked up from the book she was reading. “Bratislava? I think it’s the capital of Czechoslo—oops, I mean, Slovakia. Why?”

Jordan looked down at the envelope in his hand and smiled shyly, the grin spreading across his ten-year-old face. “Because I just got a letter from there,” he explained. He actually jumped up and down a little bit.

“Why are you getting a letter from Slovakia?” Kathy asked, mildly alarmed.

“It’s a letter from my friend Danko,” Jordan replied. “He lives there, and he’s my pen pal. I met him through my library program. He’s really cool—he plays soccer—he calls it football—and he speaks six languages! He sent me some stamps and a dollar from his country and told me that they still have castles there—look, he even sent me a picture of one!” He held out the baseball card-sized photograph. “Is it okay if I call him sometime? But I have to wait until after lunch because it’s six hours later there than it is here which means that while I’m eating lunch, he’s eating dinner. And we want to Zoom so that I can show him our house and he can show me his apartment. He lives downtown in the city! And his dad drives a city tram, which is like a train, so he gets to ride for free! That is so cool!”

IT WAS LIKE THE ISLAND OF MISFIT TOYS. Except, it was more like the island of misfit social media executives. Zuck, Musk, Durov, Mozeri, Chew, Davison, Marlinspike—the names around the table read like the partner list of a Bulgarian law firm. They were in a back room at Burkes in Santa Clara. Zuckerberg was gesturing earnestly with his hands and talking passionately, an Oculus headset on his forehead, making him look like a mutant skin diver. “It’s not too late,” he was saying. “If we use the power of the metaverse—”

“Lyubitel!” Durov spat into his Red Bull and vodka, interrupting Zuck’s earnest plea by slamming the glass onto the table. “There is no metaverse, you ass! Don’t you get it? The reason people were supposed to retreat to your goggle world was to get away from this one, and now that they’re in charge of the real world again, in charge of their own lives, making their own decisions, they don’t need us anymore. They don’t want to go there, even if they could!” Indeed. Ever since the great disappearance, the Metaverse had gone dark. Durov rose abruptly, knocking over his chair.

Musk stood in the corner with a handful of Waverly Wafers, tearing at the cellophane and mumbling to himself, stuffing them in his mouth, one at a time, looking at the others, a slight smile on his face.

ED ADAMS RE-ENTERED THE CONFERENCE ROOM after being unceremoniously asked to leave the day before by CEO Walt Harrington. Since then, Harrington had also been asked to leave, but his invitation to return wasn’t in the cards.

“Ed.” The board secretary rose to greet him, albeit awkwardly. Same way he’d greet a homeless guy on the street, I suspect, thought Ed. He ignored the proffered hand.

“Sorry about the kerfuffle yesterday.” The guy was nervous: he looked like a pigeon in traffic. “Harrington had his back up, and we were wrestling with—”

“Why am I here?” Adams interrupted. “I’m missing a date with my grandson, so I hope you have a good reason for me to be here—especially after yesterday’s ‘kerfuffle,’ as you call it.”

The secretary nodded like a bobbing timberdoodle. “Oh yes, oh yes,” he replied, falling all over himself. “You offered some ideas yesterday about how to measure our market performance without social media, but Walt shut you down (conveniently ignoring the board’s failure to shut Walt down) before you had a chance to fully explain. We’d like you to do that, please.”

The man was just this side of pleading—perhaps it even qualified as mewling. And Adams was enjoying every second of it. It reminded him of a scene from Roger Rabbit: P-p-p-leeeeeese, Eddie…

And to think that I’m the damn lawyer, he mused.

“What did we do before social media came along?” he asked abruptly.

The board members around the table looked at each other. Some stared at the wood grain of the tabletop. The chief marketing officer studiously poured himself a glass of water. No one spoke.

“Seriously? Kim, look at me. You’re the head of marketing; I’m a bloodsucking lawyer. You should be telling me how to do this, not the other way around.”

Kim Reynolds drank from his waterglass, at the same time nodding vigorously, causing narrow runnels of water to leak out between the glass and the corners of his mouth and creep down his cheeks and neck, soaking his shirt collar.

“Kim! Put down the damn glass and talk to me. You’re Marketing—what did you do before social media?”

Kim wiped his mouth on the sleeve of his jacket. “Well, we…we…we did surveys; and we placed ads in magazines and on TV and radio; and we called customers to talk with them about products,” he stammered. “We also did some email advertising and a bit of Web site placement.”

“And how well did those work?” Ed asked him.

“Well, they worked pretty well, I guess. But we had to be a lot more careful with the message when we put them out there—”

“Meaning, I assume, that the ad copy actually had to represent the characteristics and quality of the product, and how it would do good things for the customer, rather than subliminally telling customers and would-be customers what losers they were if they didn’t use the product, and then reinforcing that message of shame with social media?”

“Well…yeah,” Kim replied, looking at something very interesting on the tabletop. He still stood at his place, scared to sit.

“Kim. Sit. Social media’s gone. It no longer works. That train has left the station. Turn out the lights, the party’s over. I can play the aphorism game all day long. But here’s the drill: If you people want to stay employed, if you don’t want a shareholder revolt on your hands, if you want to create and maintain customer loyalty, then get ahead of this mess and start doing your jobs. This stuff we make doesn’t sell itself.”

“What do you propose?” asked the timberdoodle.

“Go full retail. Take advantage of the fact that people have come to expect slow service from the mail. Even though Apple owns it now, it will still be some time before they can ramp things up with their new delivery strategy. Fill the stores: fill ‘em with stock and fill ‘em with people. Do what Apple has never stopped doing: offer a customer experience that’s better than anybody else. Do what Carol Borghesi, the leadership visionary who now runs crisis response for western Canada that everybody’s talking about, said: “Just do what you said you’d do, when you said you’d do it, for the price you said you’d do it for.” It’s actually that easy.”

“Apple?” one of the women at the end of the table asked, the Comptroller, from behind the safety of her Windows Surface.

“Ed looked down and sighed. “Have you ever been in an Apple Store in a mall?” he asked the collected group.

Nobody had.

“You need to take a field trip. On the way home, I want every one of you to swing by the mall and walk into the Apple Store. You don’t have to buy anything, although I suspect you all will. Just walk in and pay attention. The first thing you’ll notice is that the store is jammed with very happy customers—you’re going to feel like you’re crashing a cocktail party that you weren’t invited to. Within seconds of walking in, somebody will approach, introduce themselves, and ask how they can help you. They may even stick an iPad in your hands to play with and walk away. If you say you’re just looking, they’ll leave you alone. Just wander around and watch the engagement. The last time I went into an Apple Store I counted 57 employees on the floor, all of them busy, and that didn’t count the people behind the scenes doing stock or inventory or whatever. That is the model we have to follow.”

AROUND THE WORLD, THINGS BEGAN TO SHIFT. The number of pedestrians struck by cars dropped precipitously as drivers left their mobile devices in their bags and purses while driving. Chiropractors specializing in neck disorders began to seek other fields of specialization, as people stood tall and straight for the first time in years. Bookmobiles began to appear once again in neighborhoods, and bookstores saw a renaissance in interest and demand. People began to gather in-person, often going on long walks together, increasingly combining their ambles with shopping excursions. Road traffic declined; as more people walked, towns began to repurpose oversized parking lots as partial green space. In one interesting case, Wal-Mart put croquet lawns in the middle of their formerly vast parking lots.

Meanwhile, as people walked more, the incidence of diabetes and obesity declined. Kids increasingly played outdoors as part of their daily routine.

Over time, the jonesing for social media that so many craved began to fade, as the metaverse faded away and the universe faded back in. Along the way, the mantra changed from ‘look-at-me look-at-me look-at-me’ to ‘talk-to-me talk-to-me talk-to-me.’ Civility grew; there was talk of a grassroots Curiosity Party taking shape in Washington. A new reality show appeared on broadcast TV; it was called, “Who Has the Richest Imagination?”

ON FEBRUARY 17TH, Twitter was acquired by Western Union; there were rumors that the company intended to turn it into a basic telegram service. Instagram was acquired from Meta by Hudson News, the owner of the National Inquirer. Facebook quietly shut down; its name was acquired by Brigham Young University.

Nobody noticed.