I’m standing on the front porch because a thunderstorm is passing through, and the sky is as dark and green as the back of a catfish. If there’s a more satisfying experience out there, I honestly don’t know what it is. The hiss of rain, the random chiming of leaves, downspouts, puddles, and flower pots as the raindrops fall, the crackle and crash of thunder—it’s nature’s best symphony. And the light—I’ve always believed that the light during a thunderstorm is something you can taste. It’s more than visible; thunderstorm light glows, from within, and it comes from everywhere and nowhere.

The best part of a thunderstorm, of course, is when it ends—not because it’s over, which I always regret, but because it leaves behind a scent trail, that amazing smell, the breath of the storm, that proves that it’s alive. That smell, which we usually call ozone, isn’t ozone at all, at least not totally. It’s a very different chemical compound that I’ll introduce you to in a minute. But first, because I brought it up, let me tell you a bit about ozone, because it is a pretty important chemical.

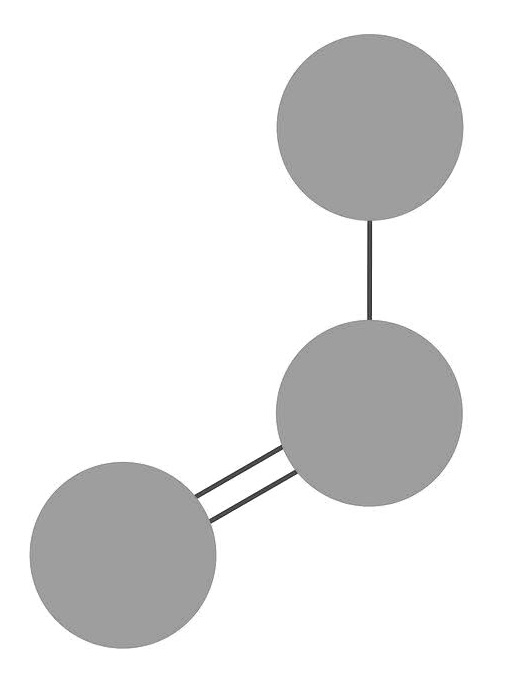

Ozone is a weird form of oxygen. Oxygen is normally a diatomic molecule, meaning that two oxygen atoms combine to form the gas that we breathe, O2. Ozone, on the other hand, is O3, a much less stable molecule.

Everybody knows about the ozone layer up there. Well, that layer exists because ultraviolet energy from space strikes the oxygen in the upper atmosphere, changing O2 to O3 and creating a layer or shell of ozone that does a very good job of shielding us from all that UV radiation that would otherwise fry us into little masses of melanoma. At least, it protects us until we do dumb human things, like release chlorofluorocarbons that chemically eat holes in the ozone layer and let all that nasty UV energy through.

The ozone layer sits about 30 kilometers above the surface of the planet, and in spite of its name, the concentration of ozone up there is only about eight parts-per-million, while the rest is mostly just regular oxygen. But it’s that oxygen that absorbs ultraviolet energy to become the ozone that protects the planet’s surface from most of the effects of harmful radiation. And while ozone has beneficial effects in the atmosphere, they’re not all that beneficial down here on earth. It’s known to reduce crop yields when there’s too much of it in the ground, and because it’s such a powerful oxidant, it can be extremely irritating to noses, throats and lungs. It can also cause cracks in rubber and plastics, and in at least one study, it’s been shown to make arterial plaque, the fatty buildup that can lead to heart attack and stroke, worse. Talk about a love-hate relationship.

So, let’s talk about what we were originally discussing before I diverted us—and that was the wonderful smell that takes over everything after a rainstorm, that smell that makes us inhale deeply and feel good about life in general.

As it turns out, that smell doesn’t come from ozone—at least not exclusively. Ozone may be in the air if there was lightning during the rainstorm, but the chemical you’re mostly smelling is called Geosmin. You smell it after a rain, or in wet dirt that you’re digging up in the garden. The smell is so recognizable, and so wonderful, that it even has a name—Petrichor. It comes from two Greek words that mean “the smell of the substance that flows in the veins of the Gods.”

So, where does Geosmin come from? Well, it turns out that it’s created as a by-product when three types of bacteria found in the soil, actinomycetes, streptomycetes, and cyanobacteria, have their way with organic material. As they break it down, Geosmin is released. So, it’s naturally occurring, and in fact contributes to the flavor of beets, spinach, lettuce, mushrooms, even that wonderful, earthy taste of catfish. Sometimes it can be overpowering when too much of it gets into water supplies, and while it isn’t harmful, it can temporarily give water a bitter taste.

Here’s one last, interesting thing about Geosmin and its Petrichor aroma. Human noses are extremely sensitive to the smell of Petrichor, in fact, more sensitive to it than just about any other compound. We can detect it in concentrations of five parts per trillion. To put that into perspective, for the human nose to detect methanol, a fairly pungent alcohol, it has to be present in concentrations of a billion parts-per-trillion. That’s quite a difference. And why are we so amazingly sensitive to it? Well, some scientists believe that that sensitivity has been genetically selected, because it allowed our distant ancestors to find water, even in the driest places on earth. No wonder it smells so good—it helped keep us alive.