Spring is a special time in Vermont: the long, dark winter begins to release its hold on things; the ground begins to thaw and soften; and suddenly, we can smell things again during our morning walks in the countryside. Birds call; people emerge from hibernation; kids ride around on bicycles, the first time since November.

Spring also heralds the arrival of two special and unique harvests in Vermont. First, of course, is maple sugaring. All over the state, sugarhouses light the fires beneath their boilers, and soon, the air is redolent with the rich, thick smell of maple, as thousands of gallons of clear sap are converted into the golden amber elixir of maple syrup. It’s a rare commodity: the rule of 86 tells us how much sap we need to make a gallon of syrup, a rule based on the percentage of syrup in the harvested sap. At the beginning of the season, that number hovers around two percent sugar. Divide that number into 86 and we know how much sap we need to create that gallon we take home from the store. That’s a lot of sap.

Marshmallum dazekiae

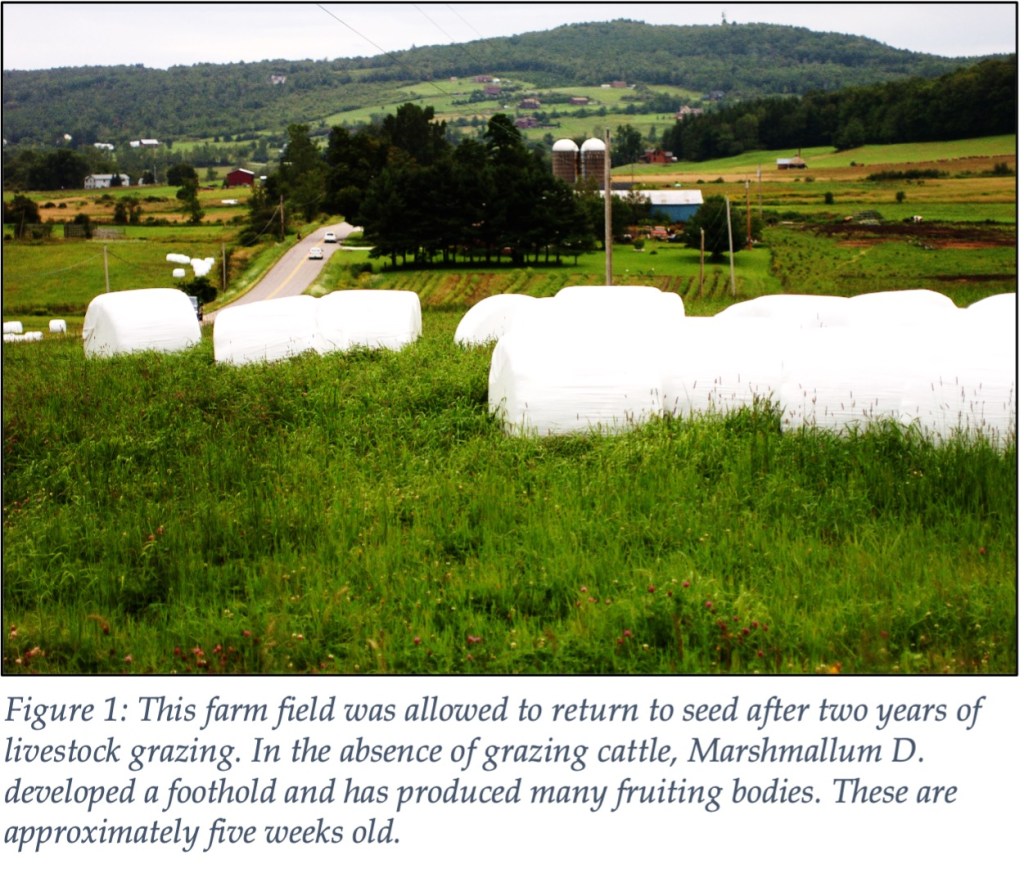

The second harvest is equally important, but less well-known. Across the state, in farm field after farm field, bulbous, snow-white growths emerge from the fallow mud and ice. At first, they go unnoticed, because they are hidden in plain sight atop extensive snowfields. But as the snow melts, and as the fruiting bodies of Marshmallum dazekiae develop and grow, they become far more conspicuous as they rise above the field. Harvesters across the state take notice and prepare for the feast: It is nearing time for the annual Vermont marshmallow harvest.

The fruiting bodies of Marshmallum d. are quite large, sometimes growing to heights of four feet and weighing more than 500 pounds. They are roughly cylindrical in shape. When they first form, the fruiting bodies lie on their sides, but as the large stem that anchors them to the plant dries, it twists as fibrous proteins in the outer sheath of the stem dry and shrink, twisting the fruiting body until it stands more or less upright on one of its flatter ends. At this younger stage of its life cycle, the fruits of Marshmallum are still quite firm, easily supporting the weight of a small animal, as shown in Figure 2.

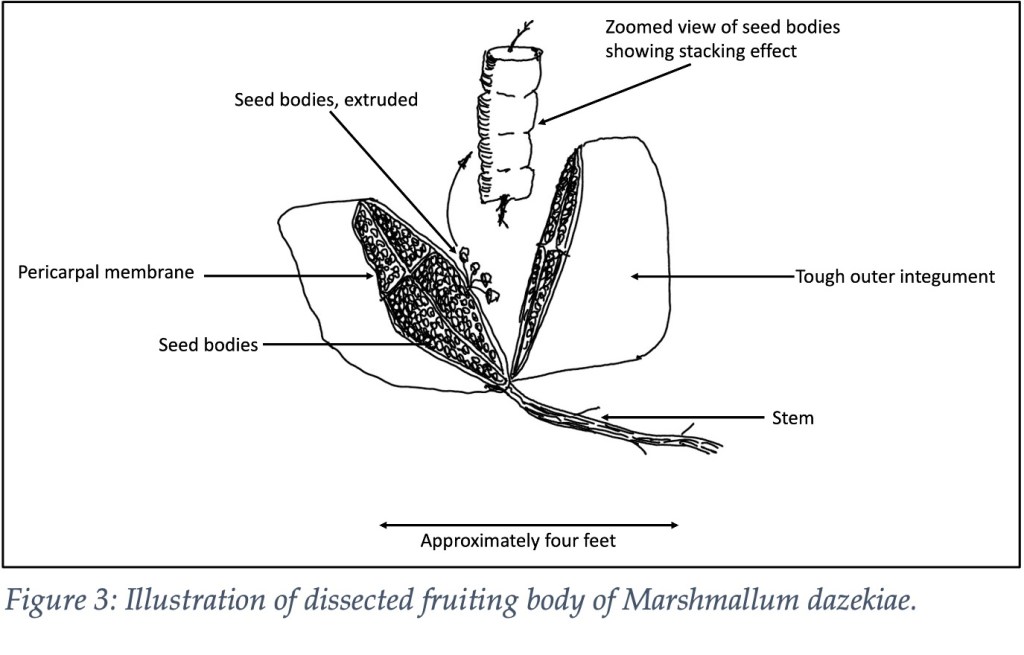

Another defining characteristic of the Marshmallum fruiting body is the thick skin that protects the cascade of embryos developing inside. The skin, characteristically a brilliant white color, is thick and difficult to tear, almost leather-like in its toughness. It resists all but the strongest claws, and while a black bear could penetrate the membrane, they typically don’t. Researchers that dissect the fruiting bodies for anatomical study have found that the easiest way to open them is with a large-bladed carpet knife; smaller, more common dissecting tools are typically insufficient for the task and dull quickly.

The fruiting body of Marshmallum d. is morphologically analogous to those of pomegranates or tomatoes, in which individual seeds within the fruiting body are nestled in protective jellylike chambers. In cross section, the fruiting body of Marshmallum (which as we noted earlier is remarkably difficult to cut) contains four main chambers, separated by tough integumental membranes, each about a quarter-inch thick. Each chamber is filled with 200-300 rows of seeds, clustered in stalks, that are protected by white, sticky flesh. The seeds are tiny—smaller than a mustard seed—and difficult to spot within their white protective covering.

A fruiting body cross-section is shown in Figure 3.

Botanical Variation

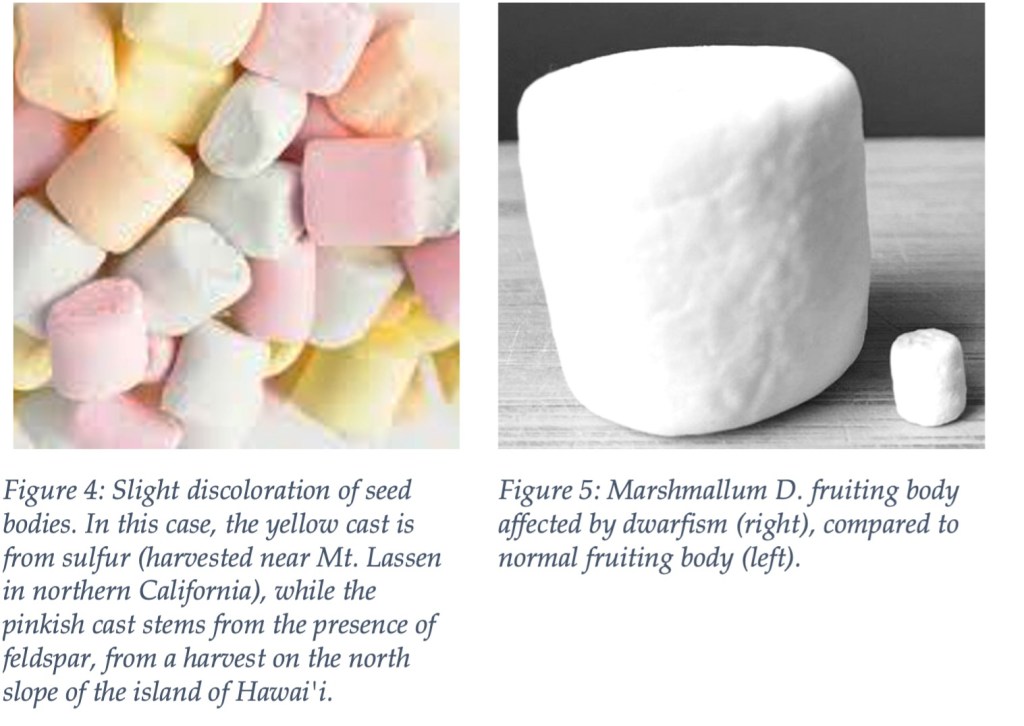

Morphologically, there is little variation in Marshmallum d. However, it has been shown that soil composition plays a role in pigmentation, particularly when certain minerals are present. Sulfur and feldspar, typically found in soils that have some degree of volcanic origin, can result in a slight color shift of the seed bodies, in particular a light yellow or pinkish cast, as shown in Figure 4. This is unusual, however; it is rare in Vermont, occurring most frequently in the smaller fields of northern California and Hawai’i.

Another variant that can occur in addition to discoloration of the normally white seed bodies is dwarfism. Typically (but not always) related to a lack of manganese in the soil, the seed bodies within the pericarpal membrane become stunted, reaching a size that is about one-eighth normal. These are shown in Figure 5.

Conclusions

Commercial opportunities for Marshmallum d. are now beginning to emerge, although large-scale production and market opportunity remains elusive. There is evidence to suggest that earlier societies may have harvested and roasted the seed pods over open fires [Kraft et. Al.] and occasionally combined them with other plant-derived substances such as raw sugars, cocoa [Hershey, 221-223] and thin crackers made from whole grains [ibid]. Perhaps insights gained from archaeological studies will yield opportunities for modern commercialization.